Hai Van Nguyen had been imprisoned before.

He’d been held for days, he says, interrogated and beaten – and told to give up the names of those organizing anti-China and anti-government protests in Vietnam.

But this time was different. The political blogger, also known as Dieu Cay, faced a closed-door trial in Ho Chi Minh City on Sept. 10, 2008.

The charge against him was tax evasion. Yet the timing was curious. He was arrested that April, days before the Olympic Torch came through on its way to Beijing.

Tax evasion, according to nongovernmental organization Human Rights Watch, was a “pretext” to keep him from protesting China. “I wasn’t scared,” Nguyen said through an interpreter. “I knew the risks.”

The verdict: guilty.

He was sentenced to 21/2 years in prison. He says he served six.

• • •

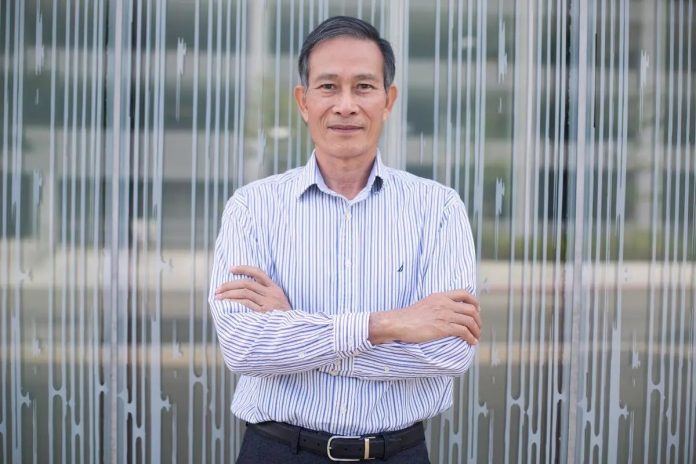

On a recent Saturday, Nguyen, 63, sat on a bench in Sid Goldstein Freedom Park in Westminster.

Nguyen spoke in a methodical near-whisper about life in Vietnam: fighting for the North, running an electronics shop in the 1990s and turning his focus toward human rights.

Human Rights Watch long has decried Vietnam as having one of the worst records in the world, saying the government “suppresses virtually all forms of political dissent.”

But even with the porous human rights record, Vietnam and the United States are increasingly coming together, diplomatically, to confront China economically and militarily. The U.S. State Department presses Vietnam on human rights when it can, but Nguyen’s story highlights the chasm between what America hopes Vietnam can become and what the country is actually like.

“They kept asking me to admit to a crime and they would go easy on me,” Nguyen said of his multiple arrests. “But I couldn’t. I did nothing wrong.”

• • •

Nguyen was born in Hai Phong, in northern Vietnam, in 1952, two years before Communist forces swept through, starting the 20-year civil war.

He was subjected to two decades of propaganda: about the horrors of capitalism and about the supposed inferiority of his southern neighbors.

“Everything is closed,” Nguyen said. “No radio, no TV, no education. Their education is only to eliminate capitalism.”

He was also subject to the rule that all adult males join the armed forces.

From the time he was 18 until Saigon fell on April 30, 1975, Nguyen pushed southward with his comrades.

“All I knew was what they told me,” Nguyen said.

The day Saigon fell, Nguyen began a two-week stay in Vung Tau, a town about 60 miles south of Saigon.

“I saw how beautiful the South was,” Nguyen said. “My eyes began to open. They had a better way of living.”

One day, Nguyen was wandering through a market when he saw a young woman working at her mother’s fruit stand. She was 18; he was 23. Nguyen went up to her and introduced himself.

Her father was a captain in the city’s police force. For the next two weeks, Nguyen hung out with the young woman and her family, having dinner with them and sharing stories with them.

“They were worried about what the Communists would do to them,” he said. “They were scared.”

Nguyen, though, was happy.

“It was an attractive time in my life,” Nguyen said, smiling. “Everything seemed beautiful.”

And then his phone rang.

It was May 11, 1975, and his superiors asked him to join them in a meeting room at headquarters. He knew what that meant.

“They took me away,” Nguyen said. “They took me away because I had a relationship with the daughter of the police captain.”

In jail, Nguyen and his fellow inmates weren’t allowed outside, had little to eat and were tortured.

Six months later, Nguyen was released and subsequently kicked out of thearmy.

“I went back to Vung Tau,” he said. “But when I got there, the girl was gone. I never saw her again.”

• • •

Nguyen eventually met someone else and married when he was 31. He moved to Ho Chi Minh City, studied electronics and opened a shop in the early 1990s.

In Westminster, at the Vietnam War Memorial, Nguyen described the tension his political involvement, beginning in 2000, caused his marriage. He and his wife divorced in 2006.

He has one daughter in Canada and a son and daughter still in Vietnam. He hasn’t seen them since he was arrested in 2008.

In the past nine months, Nguyen’s experience in Little Saigon, which has the largest concentration of Vietnamese outside of Southeast Asia, in many ways has paralleled the experiences of those who fled Vietnam after Saigon fell 40 years ago.

He is living with friends and trying to build a new life while staying connected to what is going on in his homeland.

He speaks to the Vietnamese American media about the situation back home – balancing anger against the Communist government with railing against Beijing’s aggressiveness in the South China Sea.

“I don’t have a job,” he said. “But I am still trying to focus on human rights in Vietnam.”

• • •

It started in 2000, with a blog.

Nguyen witnessed for years the poverty and oppression of his fellow citizens.

“If we don’t fight for them,” Nguyen said, “no one else will.”

Nguyen wrote about what he saw in Vietnam, he said, so people around the world could see the violations.

He joined protests and took photos. He said he saw police brutality. He helped found The Freedom Media Club.

That group began its work Sept. 9, 2007. And then his work – and danger – began in earnest.

The group staged several protests against China, including one Dec. 16, 2007, in front of the Chinese Embassy. Afterward, Nguyen walked down the street toward his home. The police stopped him.

“I was beat up,” Nguyen said. “They choked me until I passed out and threw me in a taxi. They took me to an office and beat and interrogated me.”

That didn’t stop him.

There were protests throughout December and into the new year.

“They asked me who organized the protests,” Nguyen said. “They eventually realized that I was one of the organizers.”

He was arrested, according to Human Rights Watch, at least 15 times fromSeptember 2007 to April 2008, when his longest stint in prison began.

“It’s bad enough that the Vietnamese government took an anti-China activist off the street only days before the Olympics torch passed through Ho Chi Minh City,” Elaine Pearson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch, said in a statement at the time. “But to imprison him now on questionable charges is a new low.”

He spent 21/2 years in prison, stuck in his cell without exercise time, being moved from prison to prison so he couldn’t receive visitors, undertaking hunger strikes to protest his imprisonment.

Meanwhile, police apparently targeted his family.

“They used propaganda against us,” said Tri Dung Nguyen, Nguyen’s 29-year-old son, in an email. “They called my family terrorists and reactionaries. Neighbors stayed away. People cursed my mom. … What they are doing is disgusting.”

In October 2010, guards escorted Nguyen to the gate of the prison.

“I served my time and was walking out of the prison,” Nguyen said.

“At the gate, I was arrested again.”

He was charged with tax evasion – again – and, in 2012, was sentenced to 12 years in prison and five years’ probation.

U.S. officials, including then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and President Barack Obama, came to his defense.

“We are concerned about restrictions on free expression online and the upcoming trial of the founders of the so-called Free Journalists Club,” Clinton said in 2011 during a visit to Vietnam.

Nguyen said Communist Party members continued to move him around, prison to prison, so his family couldn’t find him. They beat him up and urged him to admit to criminal activity, he said.

He continued his hunger strikes, even being hospitalized once.

Then one day, he was freed – sort of.

On Oct. 21, shortly after the United States eased an arms embargo on Vietnam, security guards removed him from his prison and put him on a shuttle.

“I was taken straight to the airport,” Nguyen said. “I was put on a plane and sent to the United States. I didn’t have a choice.”

He landed in America, was granted asylum by the U.S. government and moved to Westminster to start his new life.

Nguyen still hasn’t seen his family members in Vietnam. “They wouldn’t let me,” he said.

He says he does worry about his family and what the Hanoi government may do it because of his activism. But, Nguyen said, it is a necessary cost of fighting for what he believes in.

“Everyone has his own choices in life,” Nguyen said. “I chose to follow my heart and conscience, and fight for freedom.

“I would do it all over again,” he said.

Contact the writer: 714-704-3707 or chaire@ocregister.com