Ethnic Uighurs sit near a statue of China’s late Chairman Mao Zedong in Kashgar, Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, China, March 23, 2017.

© 2017 Reuters/Thomas Peter

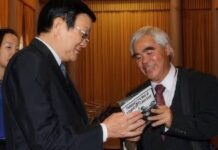

It’s not often that the leaders of democracies like Switzerland and Spain gather with the heads of repressive regimes like North Korea and Uzbekistan, but it seems no one wants to miss China’s coming-out party for its “One Belt, One Road” initiative. No fewer than 28 heads of government from Asia, Central Asia, the European Union and Africa will be in Beijing on May 14-15 for the largest One Belt, One Road meeting to date.

China’s One Belt, One Road ambitions are not modest: if it succeeds, 65 countries in Africa, Asia, and Europe will be linked by land and by sea for trade and investment.

But many key questions remain unanswered, including what kind of impact the initiative will have on human rights. Leaders attending the summit would do well to remember that international human rights norms apply across the project’s many components and participants.

The states situated along the planned trade routes have international human rights obligations, though many of the One Belt, One Road participants preside over widespread abuses. For example, in China’s western Xinjiang Province – home to 10 million Muslim Uighurs, and a key portion of the country’s “new Silk Road” – authorities have heightened surveillance and repression to prevent potential unrest that could impede One Belt, One Road plans.

Some governments in Central Asia have a poor track record when it comes to respecting rights as they relate to mega-infrastructure projects. In Tajikistan, for instance, despite some efforts by the government, residents who were resettled as part of the Rogun dam project had poor access to social services, were denied full compensation for demolished homes, and lost land for farming and raising livestock.

Even the United Kingdom – an early supporter of the Beijing-launched Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – detained peaceful protesters against Chinese President Xi Jinping during his October 2015 visit to London.

One Belt, One Road’s grand aspirations will be judged in part by how peaceful protests around them are handled by authorities: with meaningful consultation, indifference, or imprisonment?

Private companies involved in One Belt, One Road projects need to remember they have a responsibility to carry out effective human rights due diligence, as outlined under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Companies should assess human rights risks and take effective steps to mitigate or avoid those risks. Companies also have a responsibility to ensure that people who claim to experience abuses have access to appropriate remedies.

Chinese firms display a range of behavior abroad, sometimes taking steps to better comply with standards on labor, but in other circumstances continuing to engage in questionable practices. The UN Guiding Principles have been embraced around the globe, including by the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters, which recognizes that “companies shoulder the responsibility to respect human rights within their sphere of influence.”

Meanwhile, potential financiers should keep in mind their own responsibility to respect human rights as they invest in this grand plan. The AIIB is positioned to be a major financier, together with the China Development Bank and The Export-Import Bank of China. Other international financial institutions like the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank are likely to finance portions of the project at the request of individual governments.

If all One Belt, One Road participants aspire to respect human rights, the project could be truly transformative. But that will require dedicated commitment to community consultation, respect for peaceful protest, openness to reject or change projects in response to community concerns, and genuine commitment to transparency. Many participating nations do not seem naturally inclined to respond in such a manner to such challenges. Whether higher standards prevail should be the key test of One Belt, One Road’s long-term impact.

Learn about the side effects, dosages, and interactions.

how to buy lisinopril pill

The pharmacists always take the time to answer my questions.

A game-changer for those needing international medication access.

how to get cheap lisinopril price

A gem in our community.

The pharmacists are always updated with the latest in medicine.

can i buy generic clomid pills

This pharmacy has a wonderful community feel.

I appreciate the range of payment options they offer.

cost cheap clomid for sale

The best place for health consultations.