TÔI CHƯA CƯỚI VỢ MÀ!

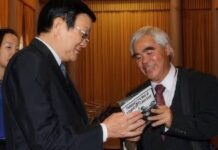

Anh chàng Martinez mới gặp linh mục Đặng Hữu Nam, ngạc nhiên nói: “Oh You look so young, I thought..” (ôi trông cha còn trẻ quá, thế mà tôi cứ tưởng…).

Cha Đặng Hữu Nam tỉnh bơ nói: “of course, I’m not getting married” (dĩ nhiên rồi, tôi chưa cưới vợ mà” ![]() 😂

😂

Tôi và Martinez cười sảng khoái vì câu đáp độc đáo của ngài.

Tính hóm hỉnh hài hước của cha Nam đã khiến không khí cuộc nói chuyện với chàng phóng viên ngoại quốc về chủ đề Formosa trở nên nhẹ nhàng hơn nó vốn có. Chính sự hài hước tự nhiên trong những câu chuyện khô khan đã làm nhiều người bất ngờ đến thú vị. Trong công việc thì nguyên tắc nhưng tương quan nhân vị thì lại tình cảm và những câu chuyện tiếu lâm luôn làm cho các vị khách cười nghiêng ngả. Thật ra đâu phải chỉ khách mới cười, anh em chúng tôi ở với cha suốt cả năm trời mà khi nào cha kể chuyện cũng cười không kịp nhặt răng.

Anh chàng Martinez trước khi về nước đã nhắn tôi: cám ơn cha và anh rất nhiều. Đây là lần đầu tiên đi làm phóng sự mà được cảm thấy như ở nhà mình.

Tôi rất vui vì nghe được tâm tình đó từ Martinez nhưng vui hơn vì học được điều đó từ cha: đón tiếp tất cả mọi người với sự nồng nhiệt và nụ cười của mình.

Mời đọc bài viết chi tiết trên tờ The Guardian về cuộc chiến của chúng tôi đòi công lý cho nạn nhân Formosa.

https://www.theguardian.com/…/vietnamese-fishermen-jobless-…

‘We are jobless because of fish poisoning’: Vietnamese fishermen battle for justice

A year after Vietnam’s worst environmental disaster, lives remain ruined while the government cracks down on protesters seeking compensation

“We used to eat the meat of the pig, but now all we have to eat is the skin” – the Vietnamese saying neatly encapsulates the predicament facing the country’s fishermen, says Nguyen Viet Thieu.

“Before the marine disaster happened, I could earn up to 15m Vietnamese dongs [£500],” reflects Nguyen. “But after, I didn’t sell any fish at all. I was sick of my profession.”

He moors and ties his small boat in the dock of Tan An village. Today, he has caught nothing.

This weekend, like every other, Nguyen and his neighbours will attend a protest vigil at the local church. It is their attempt to keep attention focused on the aftermath of the chemical spill that poisoned up to 125 miles of Vietnam’s central coastline last April. The disaster has damaged the regional economy of a country that earned $7bn (£5.4bn) from seafood exports in 2016.

Led by Catholic priests, prayers and marches have been held ever since. Despite reports of demonstrators being arrested and beaten by the authorities in Nghe An province, rallies calling for justice and government accountability have been spreading across this central region.

Families from Nghe An say their livelihoods have been destroyed by the toxic discharge from a steel plant in neighbouring Ha Tinh province. But compensation has been awarded only to people in Ha Tinh and three other adjacent provinces – Quang Binh, Quang Tri and Thua Thien-Hue.

Anger has been growing over the government’s handling of what is thought to be the country’s worst environmental disaster – affecting 450 hectares (1,112 acres) of coral reefs, of which about half were totally destroyed.

Slow government response and denials of wrongdoing sparked angry protests not often seen in four decades of Communist party rule.

In April 2016, at least 70 tonnes of dead fish were washed ashore. In July, the Formosa Ha Tinh Steel Corp, a subsidiary of Taiwan’s Formosa Plastics Group, admitted responsibility, blaming an accidental release of chemicals – including cyanide – in waste water during a test run of the plant.

Formosa Ha Tinh’s chairman, Chen Yuan-Cheng, apologised, saying: “Our company takes full responsibility and sincerely apologises to the Vietnamese people … for causing the environmental disaster that seriously affected the livelihood, production and jobs of the people and the sea environment.”

A government minister, Mai Tien Dung, told reporters Formosa Ha Tinh had pledged $500m for a cleanup and to pay compensation, which included helping fishermen find new jobs.

According to the ministry of labour, more than 40,000 workers in Vietnam who rely on fishing and tourism were directly affected and a quarter of a million people nationwide felt the repercussions of the toxic spill.

Activists and environmentalists questioned the agreement reached between the government and the company because there had been no independent evaluation of the true impact.

“It is critical to publish a chemical blacklist to be acted upon immediately,” says Hikmat Suriatanwijaya, of Greenpeace Southeast Asia. “We urge factories to disclose chemical information to facilitate supply chain transparency and create a level playing field for the industry. The Formosa disaster has shown us exactly the impact of such irresponsible and unsustainable business practice.”

The Vietnamese government did not respond to a request for comment.

In April, on the first anniversary of the spill, thousands of people occupied beaches, roads and public offices demanding justice, ocean decontamination and the shutdown of the steel plant.

Blogger Tran Minh Nhat says: “At the beginning, the government neglected the disaster despite the evidence. Now, it uses all possible means to stop affected villagers from complaining. Five people have been arrested. They are stopping citizens from seeking justice.”

Tran is on probation from a prison sentence for conducting “activities aimed at overthrowing the people’s administration”. On his blog, he reported on February’s police attack on 700 peaceful marchers in Nghe An who were on their way to submit legal complaints against Formosa, claiming $20m in damages.

Organised by clergy and lawyers, the legal struggle between fishermen and one of Vietnam’s largest investors began as soon as Nghe An province was excluded from the government restitution agreement.

“We’ve given financial support to affected families and helped them file petitions,” says Dang Huu Nam, a priest whose church has become a haven for activists. “We managed to submit more than 600 individual lawsuits at the Qy Anh court in August 2016. But there are around 5,000 villagers harmed.”

His prominent role has attracted the attention of the authorities and in August he was arrested while in Hanoi for a medical checkup. “They interrogated me for four hours and told me to stop supporting demonstrators,” he says.

To counter state-run media allegations of disagreements over anti-Formosa protests, 18 priests signed a joint statement of support. “The church stands by the side of Formosa’s victims. We’ve raised around 1bn Vietnamese dongs [£34,000] for those in need,” says Father Nguyen Nam Phong, a priest at Tai Ha church in Hanoi.

The courts have rejected all lawsuits against Formosa, citing lack of evidence. “We are jobless, four people are dead because of fish poisoning and a whale was found dead on Cua Lo beach, only 50km from here. What other proof do they need?” asks Nguyen So Menh, a fisherman from Tan An village.

Despite no official data being published and concerns that it may take decades to restore the marine ecosystem, Hanoi has declared the national seawaters clean and safe for swimming and fishing.

But a recent explosion at Formosa’s steel mill in Ha Tinh has again put pressure on the government to scrutinise the activities of foreign companies.

The Formosa conglomerate, with its $10.6bn steel complex in Ha Tinh, wants to make the mill the biggest in south-east Asia.

“We don’t earn enough to provide milk for our children and we had to borrow money from the church to pay their school fees,” says Nguyen Tha Tran, a fish-sauce seller and mother of four, from Tan An.

“The government should give compensation to all regions so that families can restore our living conditions. It should also clean up the ocean and close Formosa.”

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information.Thomasine F-R.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps to support it, our future would be much more secure.