By

After more than 10 years of petitioning the Vietnamese government, Nguyen Thi Loan (pictured above) says a huge weight has been lifted off her shoulders. Her son, Ho Duy Hai, who had been found guilty of murder in 2008 and was sitting on Vietnam’s death row for eleven years, now has another chance at life.

On November 30, 2019, the country’s highest prosecutor’s office (the Supreme People’s Procuracy, or SPP) announced that “Ho Duy Hai’s case suffered from serious procedural shortcomings that affected the quality of evidence gathered” to prosecute him.

As such, the SPP has requested that Vietnam’s Supreme Court toss out all previous rulings, including the original 2008 conviction by a Long An provincial court, as well as a 2009 appellate judgment by the Ho Chi Minh City Supreme Court of Appeals which upheld the death sentence. The SPP’s latest request also supersedes its own October 2011 refusal to halt the sentence after repeated petitions from Loan.

Ho Duy Hai’s 2008 case involves the murder of two sisters, Nguyen Thi Thu Van, 22, and Nguyen Thi Anh Hong, 24, who were killed at Cau Voi Post Office in Long An province, which borders Ho Chi Minh City to the southwest. The women, who both lived and worked at the post office, were found at the foot of a set of stairs, two meters apart, with their necks slit and their heads showing signs of blunt force trauma. The robbery and double murders occurred on the evening of January 14, 2008, about 4.5 kilometers from Hai’s house. It was not until two months later that Hai was implicated. He had known the two employees and could not provide an alibi the night of the murders. Police subsequently arrested him and charged him with murder on March 21, 2008.

Hai was only 23 when he was sentenced to death on December 1, 2008, but both he and his mother have consistently proclaimed his innocence. Though Hai could not remember clearly what he was doing the night of the murders, he claimed police beat and tortured him into falsely confessing.

Other cited shortcomings in the investigation included a lack of fingerprints at the scene of the crime to corroborate Hai’s “confession”, an inability to confirm the murder weapon(s), purchased items used to replace “lost” evidence at the scene of the crime, inconsistent witness testimonies, and a lack of time of death for the two victims to corroborate Hai being at the scene, among others.

For more than a decade, Hai’s mother petitioned all levels of government to intercede in her son’s case, even holding banners in front of the General Secretary, Prime Minister, and the President’s offices. She also enlisted the help of activists, dissidents, and human rights groups on social media to spread awareness. In December 2014, when Hai was only a day away from lethal injection, the Long An provincial court decided to temporarily suspend his sentence due to uproar over the nagging inconsistences in Hai’s case.

The case became so high-profile that National Assembly (NA) representative Le Thi Nga, who was the deputy head of the NA’s Judicial Committee at the time, became involved. She personally investigated the case’s inconsistencies, confirming that “there were serious violations committed by the police and prosecution in Hai’s case.” Her tenacity, attention to detail, and personal care for Hai’s mother has earned her praise on social media, who have held her up as a model NA representative.

If the Vietnamese Supreme Court accepts this latest SPP request, then there are two possible outcomes for Hai: his case will either be suspended and all charges dropped or he will be re-investigated and re-tried.

If the Supreme Court decides the former, then Hai will walk away from death row a free man. If it decides the latter, then Hai’s case is essentially back to square-one, as if he had just been arrested. Hai would remain in police custody (i.e. virtually imprisoned, as is Vietnamese custom for those who have been arrested but not yet charged with a crime). The murders for which he was convicted would be re-investigated by police, after which the Long An prosecutor’s office would decide whether to charge Hai with a crime. If they do, then the trial, sentencing, and appeals process would repeat itself. If they don’t, then Hai has yet another path to freedom.

Regardless of the outcome, Hai’s mother is all gratitude for what has been achieved so far: “I want to thank every soul, both inside and outside the country, for caring so deeply for Hai. I will be grateful to you all for the rest of my life, for supporting my family and walking together with us on this long path.”

Death Penalty

Wrongful Death Penalty Cases And The Families That The Inmates Left Behind

Published

2 months ago

on

September 29, 2019

Death row inmates Ho Duy Hai, Le Van Manh, Nguyen Van Chuong. Photo credits: Luat Khoa magazine

Mrs. Loan began to cry softly as she spoke to me one afternoon in late March, when I called to ask if there were any updates on her son Ho Duy Hai, who is sitting on death row in Long An province on a wrongful conviction.

“He is so young, and yet already has suffered over a decade of imprisonment,” she told me over the phone. “I want him to come back home and live a normal life. I want him to get married, and have a child. Sometimes, I just really wish to have a paternal grandchild and that both of my children could live with me like in those happy days before.”

I have been in contact with the Hai family for the past four years, since I first joined the community of Vietnamese bloggers and activists calling for the suspension of Hai’s execution in December 2014, after then President Truong Tan Sang issued an order to stop his execution. It was then that I began studying his case a bit more and learned that the evidence submitted for his conviction was invalid, and quite frankly, illegal.

For example, the local authorities wanted to ensure Hai was found guilty and so they purchased a knife at a market and marked it as “similar” to the weapon that they alleged Hai had used in committing the robbery and murder of two women. And with such “evidence,” Hai was convicted and sentenced to death in 2008, when he was a recent college graduate, and just 23-years-old.

Throughout these years, I have also gotten closer to two more families of Vietnamese who have been handed wrongful death penalties. Those include the families of Nguyen Van Chuong and Le Van Manh. These two men also were convicted and sentenced to death in their 20s with no evidence and following alleged torture by police officers. These three groups of parents meet every month in Hanoi and go together to petition the government to overturn the wrongful conviction of their sons. Each month, if they saved enough money to buy supplies, they will also visit their sons in prison. All of the men were convicted and have been kept behind bars for more than a decade.

Yet, visiting their sons is not quite an easy task because of the financial strain on these families. The words of Le Van Manh’s mother – Mrs. Viet – broke my heart during our most recent telephone call, also in March this year. “If I manage to earn enough money, then I will go to see my son, but making money to support my family is quite difficult given my age,” she told me. “So for some months, I have not been able to see Manh.”

My colleague based in Vietnam told me that catching fish and other aquatic creatures at the river near Mrs. Viet’s house was the main source of her income. Yet, her determination to fight against his unjust conviction has been so powerful.

I asked her if she was able to talk about his case when she visited him in jail. “The officers don’t like me to talk about it, but I tell Manh anyways,” she said. “Manh needs hope and the information that people have not forgotten him and are fighting for him gives him hope.”

Mr. Chinh, Nguyen Van Chuong’s father, also has the same fighting spirit. He sends me documents and updates me on Facebook about his son’s case. This year, Mr. Chinh shared with me that the Supreme People’s Procuracy Office in Hanoi contacted him and invited him to go see them. The office told Mr. Chinh that they had sent a request for a trial for cassation in Nguyen Van Chuong’s case. However, the Supreme People’s Court of Vietnam denied such a request without giving any apparent reason. The Procuracy Office used that excuse and the denial to tell Mr. Chinh to stop contacting them. However, that was not a legally sound argument. First, the office recognized that the case needed to be reviewed. Second, the law allows the office to continue sending their request, even after the denial. In fact, the Procuracy Office should continue to submit their requests for Nguyen Van Chuong and not tell his father to forget about the case.

The cost for discussing the details of their cases with their family members during visitations has been quite severe for Nguyen Van Chuong and Le Van Manh. Both of them claimed that they were shackled 24 hours a day a few times. Nguyen Van Chuong’s father also told me that Chuong was being beaten up by other inmates in his prison and being forced to sign a letter for the local authorities confessing to the murder he was convicted of. Yet, the families and the inmates did not yield in front of these pressures and they kept on petitioning for a review of their cases.

Different than Ho Duy Hai, both Chuong and Manh already had children before their conviction. But their wives could not withstand the pressure of having a spouse that was given a death penalty conviction and so they left their children to be raised by Chuong’s and Manh’s parents. The responsibility to raise the children while still trying to exonerate the two men greatly added to the burden of the two families, who are already straining to survive. The grandparents are elderly and cannot find jobs that provide a fair and reasonable income. But at the same time, they have to provide support for a lot of people in their families.

In Vietnam, there is no organization that really focuses on the issue of the anti-death penalty or that assists people with wrongful convictions. And even though I work on this issue, my non-profit organization is not recognized by the Vietnamese government and our work is classified as “reactionary” conduct. More than that, none of the death row inmates would be allowed visitations by an organization or non-family persons, not even the International Committee of the Red Cross. The inmates are shut off from society entirely and can not have any contact with people and organizations that care about their cases. In fact, visitations by independent organizations working on behalf of inmates, including those sitting on death row, was a request made by the Committee Against Torture in its concluding observations for Vietnam in 2018.

As the person who has brought these three cases before the different international law reviews, such as the Committee Against Torture and the Universal Periodic Review of Vietnam, where specific inquiries were asked about them, it is very frustrating for me that international law – such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) – had not been used for the benefit of the wrongfully-accused inmates. The Human Rights Committee (a body of independent experts that monitors implementation of the ICCPR) sadly acknowledged the fact that the covenant could not actually be implemented by the people of Vietnam in its third periodic report on Vietnam early in 2019.

The families of Hai, Chuong, and Manh don’t really have support from the public or civil society organizations that operate in Vietnam. They are almost alone during their monthly petitioning to the authorities in Hanoi. They need to find some financial resources to buy supplies to visit their sons each month. More than that, no one actually assists them with funds to buy paper and pay postage fees to send their monthly petitions. And yet, none of the parents will call for financial support from the public for their families when I spoke to them. Instead, they all told me that they just want a review of the cases in an independent court of law.

Their determination and belief in justice and rule of law always encourages and inspires me to continue to bring their cases to more people, which I will do until the day that these cases are fairly reviewed and rightfully settled.

Death Penalty

Death-Row Inmate Dang Van Hien May Get A Second Chance At Life

Published

10 months ago

on

February 20, 2019

Photo courtesy: Luat Khoa magazine, Saigon Giai Phong newspaper.

On February 18, 2019, the defense attorneys for Dang Van Hien – a farmer in Dak Nong Province who was sentenced to death in January 2018 – received a letter from the People’s Supreme Court in Hanoi, asking them to supplement further information in support of Hien’s request for a trial by cassation.

The letter is a good sign. It indicates that Hien’s case may get a review of both the law and the facts by the highest court in Vietnam.

It gives him hopes that his life could be saved.

Dang Van Hien killed three men and injured 13 others during a physical altercation between him and the workers of Long Son Investment & Commercial Company in October 2016.

The call to save Hien, whose death sentence was confirmed by an appellate court in Ho Chi Minh City last July, surprisingly, received a significant amount of public sympathy in Vietnam.

Right after the appellate court’s decision was announced, in five days, 3,500 people signed an online petition, asking the President of Vietnam to spare his life.

On July 17, 2018, the Presidential Office demanded the Chief Justice of the Supreme People’s Court, the Chief Procurator of the Supreme People’s Procuracy Office, and the Ministry of Public Security to review and report back the details of the case.

The public seemed to side with Hien and agreed that while he committed murder, there were extenuating circumstances that should save his life from execution.

Long Son had been involved in a bitter land dispute for almost a decade with the farmers living in Hien’s village, Village 1535 in Quang Truc Ward, Tuy Duc District, a remote area deep into the forest of Dak Nong Province.

Dang Van Hien’s case was an agonizing tale of a farmer who started from scratch, trying to build a life on a piece of land which representing the hard-earned money that he and his wife had worked so hard for.

He was a member of the Nung ethnic minority in Vietnam who had very limited education.

But Hien believed in working hard and to this day, believed in the legal system.

He tried to petition to the central government to resolve the dispute between him and Long Son company for almost ten years.

He was not the instigator of the deadly event happened on October 23, 2016.

He earnestly believed that he was protecting his land and his family when they were attacked by the company’s workers, with bulldozers and self-made weaponry.

He turned himself into the police, believing that the law would be fair to him. He and his family tried to compensate the families of the victims for their losses.

Those were the extenuating circumstances that 3,500 Vietnamese people believed should spare Dang Van Hien’s life.

But their sympathy could have also come from the fact that land disputes have become one of the most pressing social and political problems in Vietnam during the past three decades, ever since the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) started to implement their economic reforms under the Doi Moi policy in the late 1980s.

The growth of both the private sector and quasi-government enterprises crashed head-on with landowners across the country in many development projects throughout the years.

On top of that, the legal framework involving land rights in Vietnam is extremely complicated, yet still could not resolve the most important issue confronting the authorities.

How to balance the communist concept that all lands supposedly belong to the people and still be able to justify the granting of the right to occupy and use the land to preferably private companies over a regular person?

In recent years, story after story continuously exposed incidents of local government in Vietnam giving the conglomerates a more favored treatment when granting them land use rights in real estate development projects.

The victims of the wrongful, forced removals under the Thu Thiem Project in Ho Chi Minh City had spent over 20 years in petitioning their cases to no avail.

Just last month, Sun Group – one of the largest real estate development companies in Vietnam – faced an accusation from environmental activists that they are building a resort in the heart of the country’s famous national park, Tam Dao.

Land-grabbing has become the reality that the majority of Vietnamese people acknowledges. When conflicts happen, it would be somewhat natural for them to act more sympathetic towards the land-lost victims.

There is always the possibility that anyone in Vietnam could be the next victims of land-grabbing activities, as seen in the case of Loc Hung Vegetable Garden this year, which may also explain this sympathetic reaction from the public as seen in Hien’s case.

In Hien’s case, their sympathy may get him a second chance at life.

Death Penalty

Death Penalty Remains “State Secret” In Vietnam

Published

10 months ago

on

January 24, 2019

Photo courtesy: UN WebTV

A representative from the Ministry of Justice of Vietnam said during the country’s third Universal Periodic Review (UPR) held on January 22, 2019, in Geneva, Switzerland, that “data concerning the death penalty are related to other legal regulations involving the protection of state secrets in our country. In practice, after taking many points of view from society and other reasons into consideration, Vietnam will not publicize the data concerning the death penalty.”

However, later during the same speech, the speaker seemed to have contradicted her earlier statement when she said that executions in Vietnam are “very public and would be conducted according to the requirements under the Code of Criminal Procedures.”

She did not offer any further explanation as to why the executions are public, but the data concerning the number of executions remains a state secret?

None of the information concerning the execution of inmates is mentioned in the categories listed as “state secrets” in either the Ordinance on Protecting State Secret (link in Vietnamese) or the more recent Law on Protecting State Secret (link in Vietnamese).

However, with the vague language in both of these laws, coupled with the full range of authority given to various government ministries and departments in determining what would be “state secret,” any matter of public concerns could be classified as a “secret” in Vietnam without any further explanation.

In February 2017, the Ministry of Public Security (the national police force) – for the first time – released a report, stating that between 2011-2016, Vietnam was holding 1,134 people on death row and that from 2013-2016, 429 people were executed by lethal injection.

The name of the lethal drugs, however, was not disclosed.

To date, death-row inmates are continued to be executed by unknown drugs and undisclosed procedures.

The MPS’ report in 2017 was also the first and last of its kind.

While Vietnam agreed, since the last UPR cycle in 2014, to push for reforms towards greater transparency around the issue of the death penalty, the answer from its Ministry of Justice on Tuesday seemed to suggest that the public would continue to be kept in the dark.

The representative from Vietnam’s delegate also claimed that the death penalty is only applied to the most serious crimes under the definition of Article 6(2) of the ICCPR (International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights).

This is not quite correct.

There are at least four crimes subjected to the death penalty under the 2015 Penal Code, that do not fall under Article 6(2): Article 109 (subversion against the State), Article 110 (espionage), Article 353 (embezzlement), and Article 354 (receiving bribes).

Among them, Article 109 (formerly 79) had been used almost exclusively against political dissidents during the past decades.

Vietnam also maintains the death penalty for a handful of drugs-related crime in direct violation of Article 6, ICCPR.

Vietnam scored 35 points out of 100 on the 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index reported by Transparency International. In a country where the majority of its citizens perceived corruption had plagued all levels of government, keeping information concerning the death penalty a secret from the people could raise suspicion about possible wrongdoing.

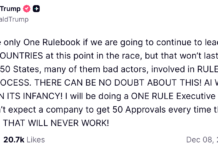

On a Facebook’s post by attorney and dissident Le Cong Dinh earlier today regarding the Vietnamese government’s position on the transparency of the death penalty, people did not hesitate to state that they believed if a death-row inmate agreed to pay a bribe, they could escape execution.

https://www.facebook.com/thanhtam.nguyen.52643/videos/2871053572925288/