By Thái Hạo — International Edition

By Thái Hạo — International Edition

In Nguyễn Khải’s short story A Hanoi Native, there is a figure who appears briefly yet lingers in the reader’s mind: Dũng, the son of Aunt Hiền. Returning home in 1975 after the war’s end, he is invited at a family gathering to share something joyful about victory. His answer is disarmingly simple: “There is not much joy.”

Dũng explains that he has spent half a year thinking about the 660 young men who left Hanoi a decade earlier. Only about forty remain. His sorrow—tinged with guilt for surviving where others did not—is not a political statement but a human one. It is the quiet burden borne by someone who returns from war with the knowledge that most will never return at all.

This grief contrasts sharply with the narrator of the story, who is flushed with triumph and self-importance. Faced with his exuberance, everyone else remains silent—an eloquent form of restraint characteristic of old Hanoi: a cultural tact that refuses to challenge pride with pain.

Two decades ago, this story was added to Vietnam’s national high-school curriculum. What redeems its narrator is his slow, shame-tinged awakening: he eventually recognizes in the Hanoians around him a cultural depth, dignity, and refinement he calls “grains of gold”—precious things he fears will someday sink into the soil and be lost.

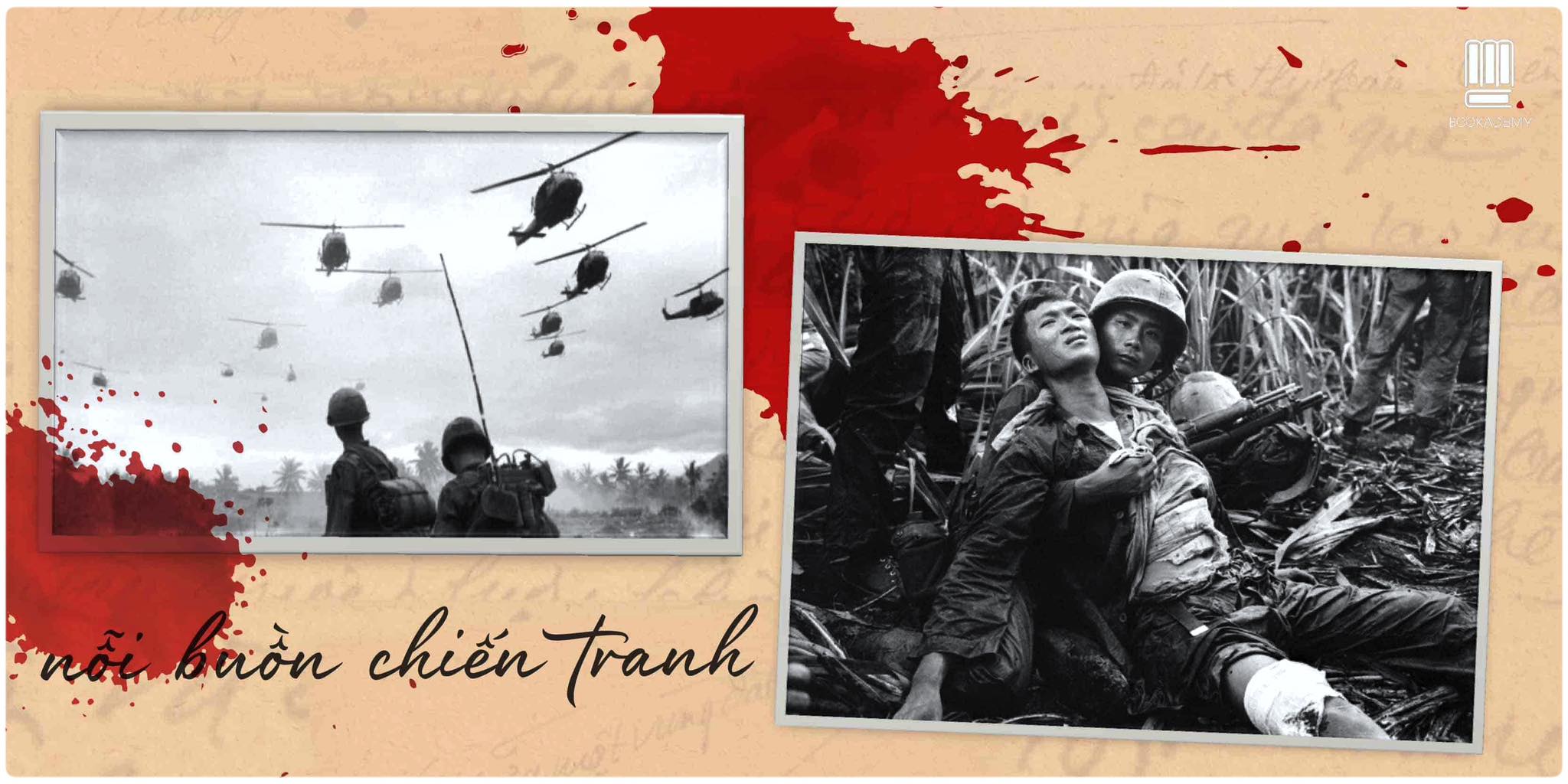

The Sorrow of War and A Hanoi Native were written only a few years apart. One is a novel, the other a short story, but both belong unmistakably to literature. Which raises a question that hovers over the recent uproar surrounding Bảo Ninh’s novel: among those loudly condemning it, how many have truly read it? And among those who have, how many have read it as literature rather than as journalism, political doctrine, or historical documentation?

The rhetoric surrounding The Sorrow of War—invocations of ideology, nation, and the soldier—rarely engages the text itself. What is often missing is the simple act of reading: alone, at night, in the silence in which literature actually speaks—where the lives in the novel cease to be “positions” or “messages” and become human beings with friendships, wounds, delirious laughter, and uncontainable grief.

Like Dũng in A Hanoi Native, Kiên—the protagonist of The Sorrow of War—is a man marked by sorrow. He reflects that war, for all its brutality, gave him comrades of extraordinary goodness; but the price of that “good fortune” was the loss of all who mattered most. Friends died before his eyes, in his arms, sometimes because of his own mistakes. Many died to save him. His survival is inseparable from the deaths of others.

What, then, could joy possibly mean?

To suggest that such reflections “distort” history is to misunderstand the nature of literature. Bảo Ninh is not revising historical facts; he is giving voice to the inner life of someone who has survived the unendurable. Literature does not produce manifestos. It does not serve as a substitute for political resolutions. Its irreplaceable function is to awaken aesthetic and moral feeling—the very capacity that modern life, busy and utilitarian, so often erodes.

In wartime, amid the intoxication of purpose and the fever of sacrifice, literature holds a fragment of experience like a shard of mirror: preserving a moment of pain, a tremor of vulnerability, a fleeting clarity. In that moment, a person becomes more fully human. Without it, they are reduced to roles—soldier, cadre, worker, instrument of ideology.

Vietnamese literary history offers many examples of suspicion toward emotional depth. Hữu Loan’s elegy The Purple Color of Sim Flowers brought him punishment for being “sentimental.” Quang Dũng’s Tây Tiến was shadowed for decades by the accusation that its portrayals of death lacked ideological triumph. Yet time vindicated both writers, not because their works served doctrine but because they preserved human complexity.

Literature flourishes only where there is an audience capable of receiving it. Vietnam has individual readers—quiet, scattered, contemplative—but not yet a broad literary public. The current backlash against The Sorrow of War reveals not a failure of the work, but a reading culture still shaped by wartime binaries: victory and defeat, right and wrong, friend and enemy. Even in peacetime, people remain trapped in the mental terrain of conflict.

Confronted with a novel, many do not listen to the characters or to themselves. They search instead for historical accuracy, ideological alignment, or logical proof. In that moment, literature becomes another battlefield. They lose the chance to meet themselves in the mirror of a human story.

Someone once asked me whether I liked The Sorrow of War. Not exactly. I struggled with it, revisited it many times. My preference is for writing that leaves space, that withholds rather than elaborates. But I must admit: there are passages in this novel that are devastatingly beautiful—pages that illuminate the darkest corners of human experience with a fragile, painful light.

Whatever debates may arise, The Sorrow of War will remain a defining work of modern Vietnamese literature—not because it flatters ideology, but because it enlarges the territory of human feeling.

I write not to join a futile argument, but for those who read literature—the ones who seek, through the page, a way back into themselves.

— Thái Hạo (international edition)