Mai Khoi, the “Lady Gaga of Vietnam,” wants that country’s vigilante force kicked off Facebook. The company told her the group is well within its rules.

For the past two years, Do Nguyen Mai Khoi has been trying painfully, futilely, to get Facebook to care about Vietnam. The Vietnamese singer and pro-democracy activist, known best simply as Mai Khoi, has tried tirelessly to warn the company of a thousands-strong pro-government Facebook group of police, military, and other Communist party loyalists who collaborate to get online dissidents booted and offline dissidents jailed. Her evidence of the group’s activity is ample, her arguments are clear, and despite the constant risk of reprisal from her own country’s leadership, her determination seemingly inexhaustible. The only problem is that Facebook doesn’t seem interested at all.

Facebook, once briefly heralded as a godsend for a country like Vietnam, where social media allows citizens to squeeze past the state’s censorship stranglehold on traditional media, has now become just another means of strangulation. Private groups filled with government partisans coordinate takedown campaigns — or worse — against any views deemed “reactionary” by the Vietnamese state, while Facebook continues to do little but pay lip service to ideals of free expression. The Intercept was able to gain access to one such closed-door Vietnamese censorship brigade, named “E47,” where it’s obvious, through Facebook’s apparent indifference, that the company has failed its users terribly.

E47 is just one example among a global constellation of state-affiliated internet censor squads both in Vietnam and around the world, but Facebook’s failure to stand up to the group should worry dissidents regardless of nationality, particularly those who might have bought into the company’s promises in the past. In an October 2019 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, CEO Mark Zuckerberg declared that “Facebook stands for free expression” and that “in a democracy, a private company shouldn’t have the power to censor politicians or the news.” COO Sheryl Sandberg testified under oath before Congress that the company “would only operate in a country when we can do so in keeping with our values.” But an investigation by The Intercept shows that this public veneration of free expression exists in a different universe from the company’s behind-the-scenes practices.

To ensure that it continues to enjoy a dominant, highly lucrative share share of Vietnam’s corner of the internet — reportedly worth $1 billion annually — Facebook increasingly complies with content removal requests submitted by the country’s government on the basis that the content itself is illegal in Vietnam. It’s a form of censorship employed by governments worldwide, and one that Vietnam seems to have played hardball to enforce: In April, Reuters reported that the Vietnamese government slowed Facebook’s servers to the point of inoperability, leading Facebook to agree to comply with more official takedown requests.

But as Mai Khoi discovered, Vietnamese Facebook is also plagued by unofficial censorship, achieved not by declaring content illegal but by coordinating users to flag it for violating Facebook’s own content rules, known as the “Community Standards.” This dupes Facebook into removing ordinary political speech as though it were hate speech, violent incitement, or gory video.

Facebook is duped into removing ordinary political speech as though it were violent incitement. It has a vested interest in acceding to these tactics.

Private Facebook groups like E47 not only conspire to disappear unwanted political speech from the site, but they also collaborate directly with the Vietnamese state security apparatus to bring online harassment into the real world, according to The Intercept’s investigation and interviews with regional experts. Through Facebook, the ability to observe one’s neighbors and then rat them out in secret is streamlined and flattened, rendered absolutely frictionless, to use a term of Silicon Valley endearment.

Facebook has a vested interest in acceding to unofficial, backdoor takedown tactics. When posts are deemed in violation of a local law and removed through official channels, Facebook suffers public embarrassment since it tallies such legal “content restrictions” in a biannual transparency report. But when such speech is removed through Facebook’s content moderation policies — inscrutable, ever-changing, and ripe for exploitation — the removal receives no public acknowledgment; it simply vanishes. This provides a route through which Facebook can trade its public interest in free speech for access to the Vietnam market, turning the internet’s democratizing potential upside down.

“Facebook was once viewed as the great hope for freedom of expression in Vietnam,” Ming Yu Hah, deputy regional campaign manager at Amnesty International, told The Intercept. “Today, increased censorship is rapidly changing this. Amnesty has documented dozens of cases of arbitrary arrests and prosecutions, assaults, and other forms of offline attacks in connection with online speech. Any individual who exposes human rights violations, or who shines a light on alleged corruption or abuse of power, or who simply challenges the narrative of the Communist Party is likely to find themselves in the firing line.”

Through spokesperson Drew Pusateri, Facebook declined to comment for this article. A Facebook manager told Mai Khoi that the company’s options against E47 were limited because the group operated without fabricating or masking the identities of members.

The “Lady Gaga of Vietnam” vs. Facebook

While Mai Khoi is frequently described as the “Lady Gaga of Vietnam” on account of her stirring voice, comparisons to Pussy Riot are perhaps even more apt: Like the Russian group, Mai Khoi’s dogged, unflinching criticism of the repressive regime that dominates her home country has made her a target. In 2018, following her European tour for a new release, Vietnamese police detained and interrogated her for eight hours, an incident that came on top of a string of raided concerts, evictions, and confiscated albums. There was a time when it seemed like Facebook could help people like Mai Khoi: “When police raided my concerts and I was banned from singing, Facebook allowed me to circumvent the censorship system and release my new album online,” she recounted in a 2018 Washington Post op-ed. “But I have also seen how Facebook can be used to silence dissent.”

Since then, Mai Khoi has taken aim at Facebook with the same dissident spirit that’s made her an enemy of the Vietnamese state, demanding reform from another powerful, opaque mega-bureaucracy — this one headquartered in Menlo Park rather than Hanoi. Facebook, in Mai Khoi’s estimation, has switched from a potential engine of free speech and political dynamism to an extraordinarily powerful engine of censorship and coercion.

Although Mai Khoi managed to leverage her celebrity into a string of meetings and exchanges with Facebook executives that any activist could tell you is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain, she now says the company has spent the past two years more or less blowing her off, providing only empty assurances and principled platitudes in response to her lobbying. Meanwhile, her fellow dissidents, activists, and journalists in Vietnam continue to be punished and menaced via Facebook, and no matter how much evidence Mai Khoi brings to Facebook’s attention, nothing changes. For over two years, Facebook has been telling Mai Khoi that the company understands her concerns, it’s committed to human rights, and it is determined to make platform safe for free expression. And for those same two years, private Facebook groups like E47, dedicated to making peaceful dissent an impossibility for tens of millions of internet-connected Vietnamese, continued to operate freely, as they do today.

The name E47 is an apparent reference to the Vietnamese military’s “Force 47” brigade, which state media announced in 2017 would deploy a staff of 10,000 to “fight proactively against the wrong views” found online. E47 was created on the same day. “As many forces and countries are talking about a real war in cyberspace, [Vietnam] should also stand ready to fight against wrongful views in every second, minute and hour,” Gen. Nguyen Trong Nghia said of Force 47 at the time, according to the Wall Street Journal.

It’s unknown to what extent E47 is an official operation of the Vietnamese state, or even operated by Force 47 itself. In Vietnam, both social media battalions and zealous Communist Party volunteers share many of the same methods, motives, and targets, making their campaigns difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate from the outside. In practice, the boundaries between a formally organized Army censorship squad like Force 47 and volunteer brigades (like E47) known as du luan vien may be thin to the point of nonexistent, with almost total overlap in terms of methods, targets, and motives. Years before the formation of E47, Vietnam’s propaganda office employed hundreds of online “opinion shapers,” as The Verge reported, and their relationship to pro-government groups on Facebook was unclear.

Hah told The Intercept that Vietnamese “authorities have employed all methods available to further their censorship and surveillance,” employing both official, “legal” takedowns and tactics associated with troll farms to maximize the suppression of speech. “Du luan vien or ‘public opinion shapers’ are people recruited and managed by the Communist Party of Vietnam’s Department of Propaganda,” said Hah. “Their role is to protect the government from online criticism through surveillance, monitoring, trolling of critics, and spreading pro-CPV propaganda. We understand that they are often recruited from among young CPV members and Ho Chi Minh’s Communist Youth Union. Although their operations and responsibilities are opaque, we believe that they carry out many similar functions to state ‘cyber-troops’ such as Force 47.”

Some E47 members do use false names, in violation of Facebook policy, but many others don’t bother. Whether or not E47 is formally part of the state, the state is well represented: Vietnamese military and police officers appear to be among its most active members, albeit on their personal accounts. One can often click through a post on E47 to find the author’s photos clearly identifying them smiling at work in a police station or posing next to artillery in their Army uniform, name tags clearly legible. Alongside them are several members of the Vietnamese press, including two editors of popular newspaper Ngày Nay and the state-run outlet VnExpress that serve as group administrators — this despite the fact that E47’s activities include suppressing the views of dissenting journalists and bloggers.

Working more or less in internet broad daylight, E47 members seem able to completely bypass a Facebook rule used against Russian government social media rings of the sort that attempted to influence the 2016 presidential election. Facebook cracked down on such operations by targeting the fabricated identities they relied upon, banning what it calls “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” E47 appears to use “authentic” accounts with real names and real pictures, short-circuiting the “inauthentic behavior” rules. By simply not operating exactly the way Russian troll farms operated four years ago, groups like E47 can cause demonstrable, real-world harm of a degree the Russians never accomplished while avoiding the company’s much-ballyhooed post-2016 crackdown on governmental meddling.

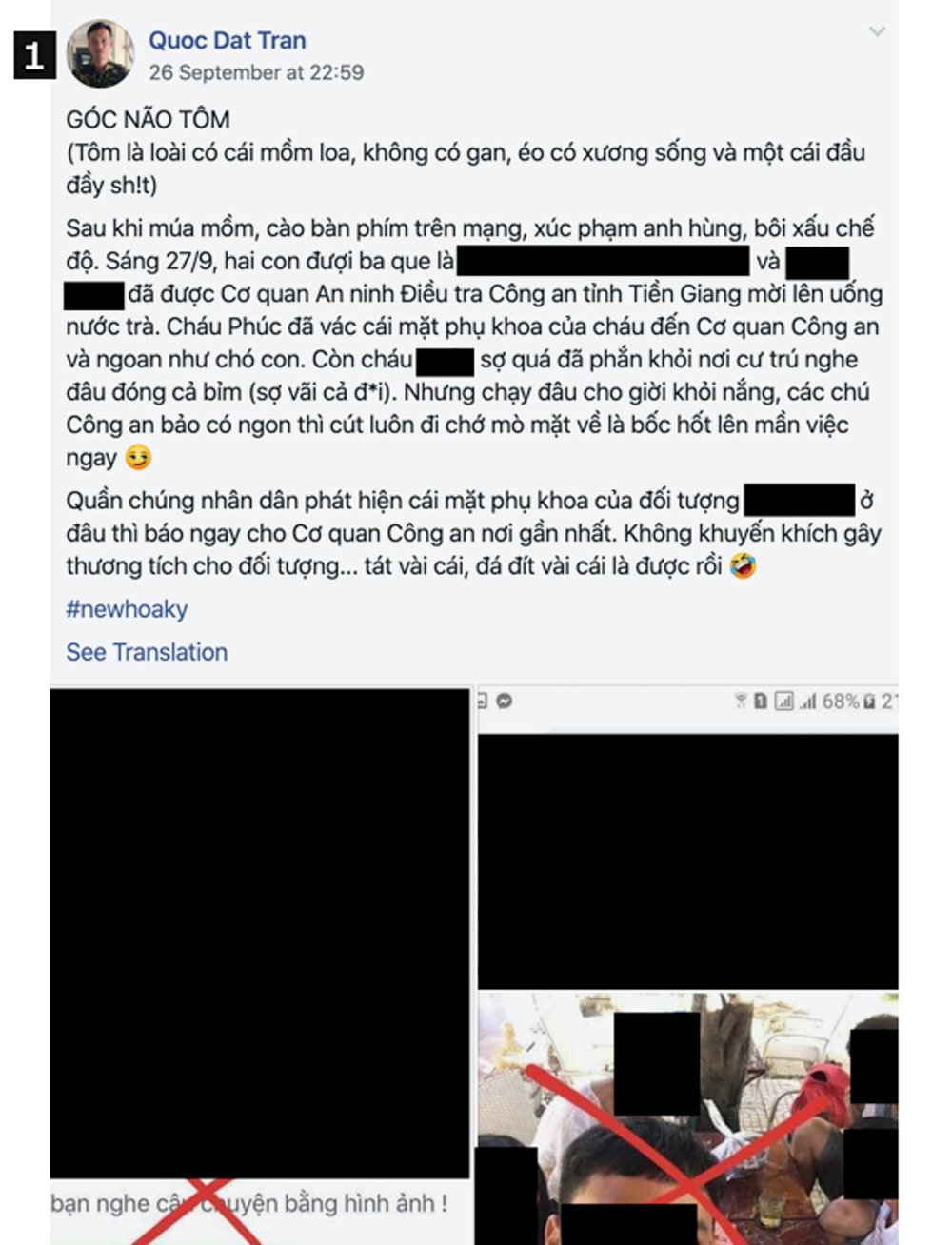

1 Quoc Dat Tran

After defaming heroes, insulting the party, inD [sic] the morning of 27th September, [redacted] and [redacted] was [sic] “invited for tea” by the Investigative police of Tien Giang. [Redacted] had shown his face at the police station like a puppy. [Redacted] had escaped from his place.

If anyone has seen [redacted] anywhere, report to the nearest police station. Not encourage injuring the suspect … but a feel [sic] slaps or kicks are good.

#newamerica

We Went Inside a Cyber Army

The Intercept accessed the invitation-only E47 group in order to corroborate and document the group’s activities, revealing a disarmingly casual environment, without any of the cloak-and-dagger material one might associate with an anti-dissident conspiracy. E47 feels far more like a group of friends than a cabal of censors: Jokes, memes, and off-topic debate were interspersed with attempts to get Vietnamese dissidents and foreign journalists expelled from the platform or to have links to their work erased. The social hijinks belie a smoothly operated machine for squashing dissent: An E47 member shares a target, often a politically dissident writer or publication, essentially nominating them for censorship. The call to arms is often accompanied with an image of the target with a red “X” drawn over it to drive home the point. From there, anyone interested in helping punish the offending journalist, activist, or ordinary citizen deemed a reactionary need only follow the provided link to the post in question and report it for violating of the Facebook’s ever-pliable Community Standards, whether or not the rules were broken. Though Facebook regularly touts the investments it’s made across the world in expanding its human and algorithmic moderation capacity, E47 has found immense success in gaming the system and reporting political speech en masse for terms of service violations, disappearing it from the web and silencing its authors without recourse.

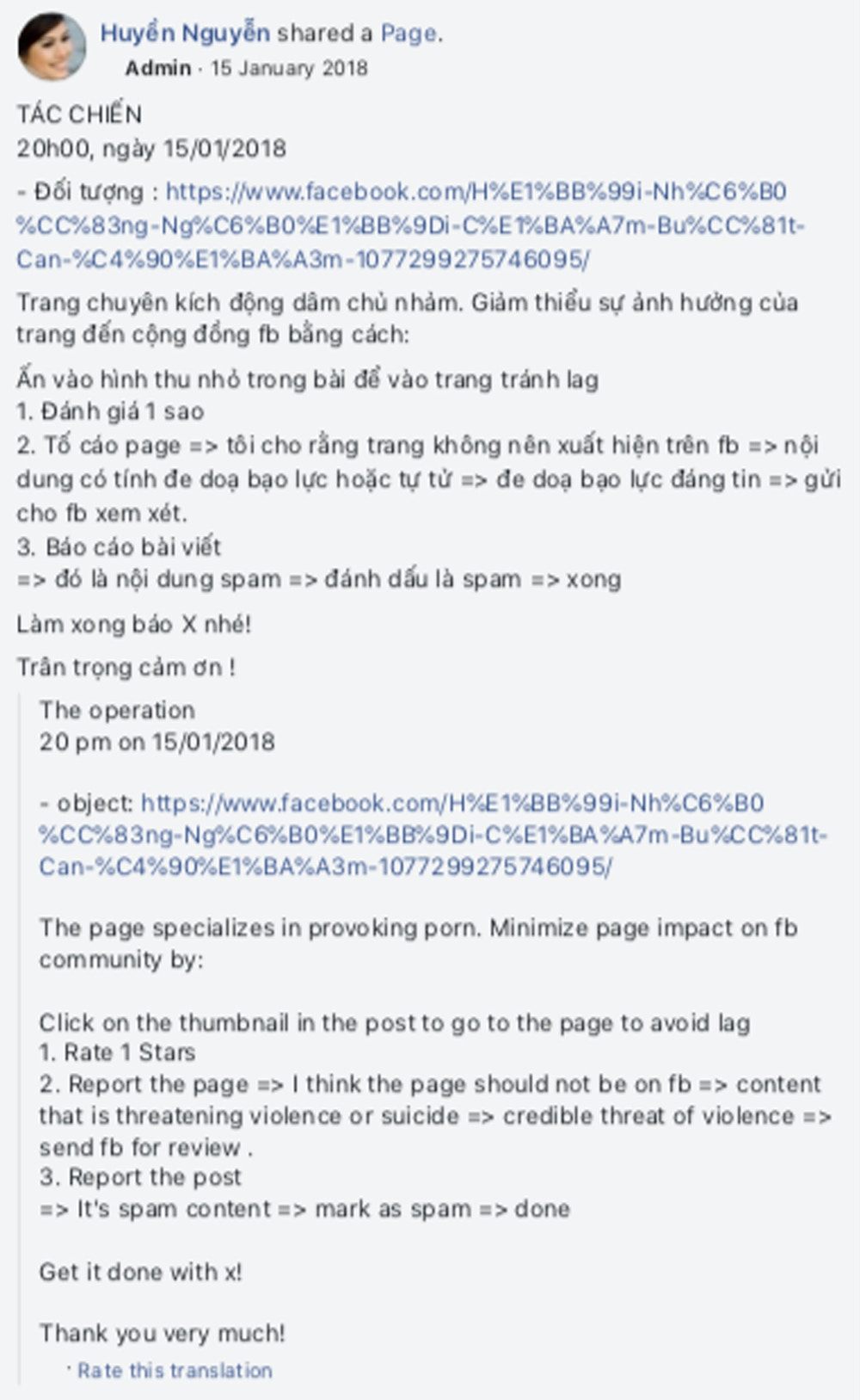

Though suppression tactics vary slightly over time and from target to target, E47’s execution of what it calls tac chien, or “targeted operations,” generally follow the same playbook: submitting false report after false report in such great numbers that Facebook deletes an innocuous post or page as if it were actually violating some rule. In a January 2018 post to the group, an E47 administrator identifying themselves as Huyen Nguyen laid out one such foolproof method for squashing Facebook speech. The three-step process on “how to fight” with Facebook’s built-in tools is simple and intuitive: For a targeted Facebook page, E47 users are asked to rate it with one star out of five, falsely flag the page’s posts as containing either a credible threat of violence or suicide, and then report the page itself as spam. Other E47 targeted operations ask the group’s over 3,400 members to falsely report other Community Standards violations like pornography — then spam the target page with actual rule-breaking violent or pornographic comments, essentially planting evidence of a bannable offense.

Screenshot: Obtained by The Intercept

E47’s leaders often urge their foot soldiers to use a virtual private network when participating in a Facebook raid, allowing them to route their internet traffic through a server in the United States to mask their real IP address and geographic location inside Vietnam. As a final gesture of troll army esprit de corps, E47 members typically leave a screenshot commemorating their bogus Community Standards report, cheering each other on and providing cheekily militaristic updates (“Report completed mission, over”) or sometimes simply commenting “RIP.”

But a locked Facebook page can sometimes be the least of E47’s damage. A January 2019 E47 memo by Nguyen titled, “The Process of Eliminating Reactionaries on the Internet” shows how online hostilities are only one prong of attack. Nguyen encouraged group members to compile dossiers on dissidents and regime critics, tracking not only their offending words, cross-referenced with potential violations of Vietnamese law, but also personal details like where they live and work. Nguyen’s post encouraged cadre members to not only report E47’s targets to their local police, but also noted that the group’s administrators would personally report individual conduct to people inside the Vietnamese Ministry of Public Security. “There are very serious real-life consequences of troll groups” in Vietnam, said Brad Adams, head of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division, in an email to The Intercept, citing instances of “physical harassment of dissidents” targeted on Facebook. E47 is no exception and regularly instructs its members to track the whereabouts of its enemies so that they can be dealt with offline.

Multiple posts reviewed by The Intercept show E47 members asking for help identifying or in some cases physically locating local “reactionaries,” often people accused of criticizing the police or who’ve taken part in a real-world protest. In one June 2018 post, an E47 member shared the profile of activist Nguyen Quoc Duc Vuong, accused of participating in an unspecified Ho Chi Minh City protest, adding that they hoped local police could investigate. A man identifying himself as a police officer in Vietnam’s Lam Dong province quickly volunteered; a little over a year later, Human Rights Watch reported that Vuong, who’d “participated in a major protest in Ho Chi Minh City against the draft law on special economic zones and the newly passed cybersecurity law,” had been arrested over his Facebook posts. Fittingly, when Vietnam passed that landmark 2018 “cybersecurity” law, widely criticized for granting the state a carte blanche ability to delete dissenting speech online, E47 tasked its members with screenshotting “reactionary” comments left on a state newspaper article discussing the legislation so that their authors could be later targeted.

Screenshot: Obtained by The Intercept

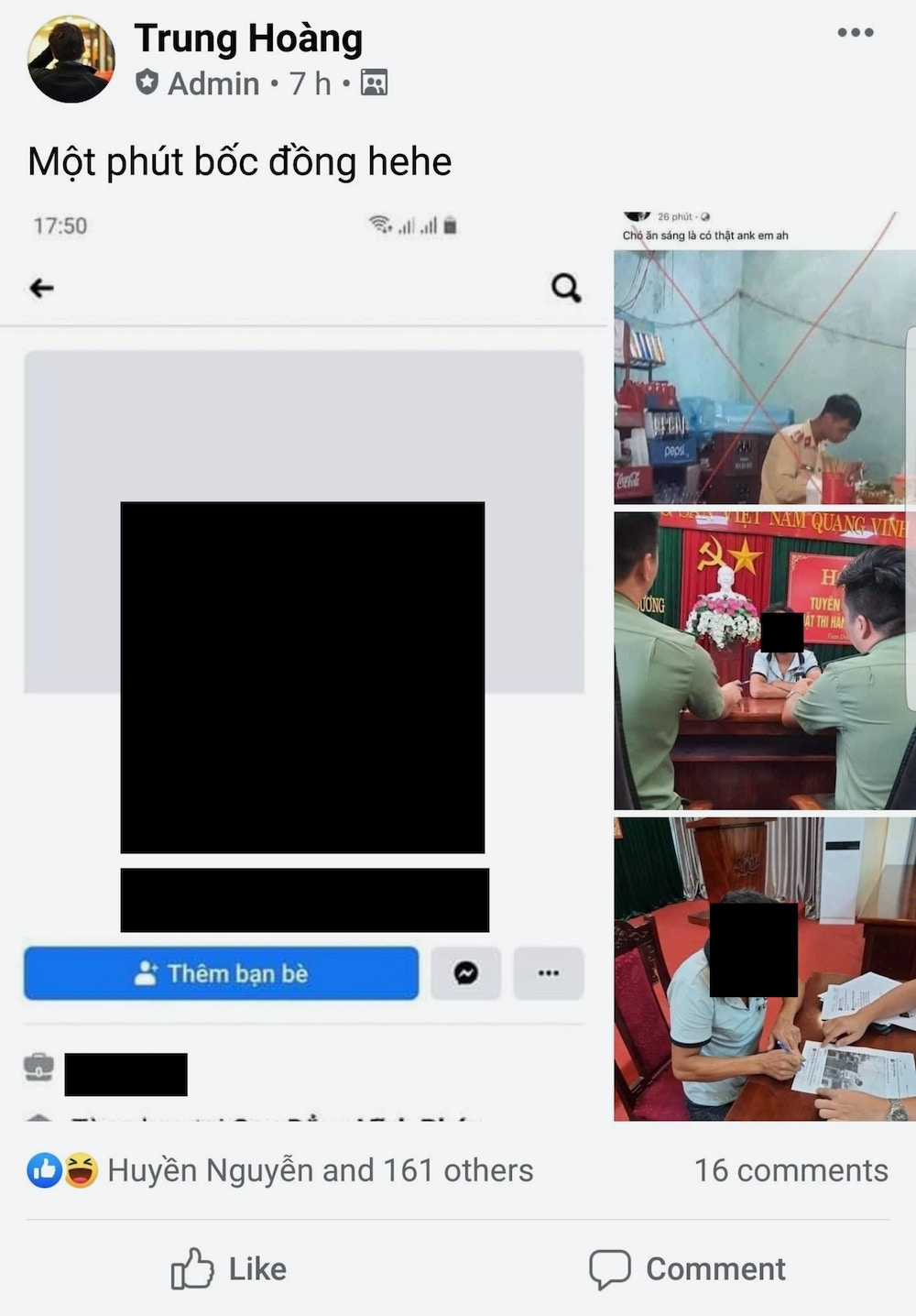

In another case, complaints shared to E47 about a Hanoi citizen who mouthed off to a traffic cop quickly resulted in the man’s arrest, according to a post in the group sharing photos of the man’s detention and interrogation. Another series of posts showed how E47 had a different Hanoi man detained, again for mocking the police. That man’s offense was a creating a Facebook post showing an officer dining alone, captioned (in Vietnamese), “A dog eating breakfast.” An E47 member messaged the post directly to a police officer, and the man was subsequently detained and made to sign a printed copy of the post. Images of the proceedings were posted right back to E47 to members’ delight.

On another occasion, members of E47 conspired to target the Facebook page of the Association of Brave Writers, a Vietnamese political dissident group, filing false reports claiming that the group promoted violence and suicide, and soon thereafter discovered they had apparently been successful: The association’s page had been locked and rendered inaccessible. Several months later, the group’s page was accessible once more, but in June 2018 the organization told its followers that because it had been reported to and penalized by Facebook so many times, the organization was moving to a different website altogether.

Facebook’s global reach makes it easy for E47 to punish profiles beyond Vietnam’s borders. The popular Vietnamese blogger Nguyen Ngoc Nhu Quynh, also known as “Mother Mushroom,” wrote a string of articles on environmental destruction and state corruption, leading to her 2016 arrest for “conducting propaganda against the state and two years of imprisonment. She was released in 2018, went into exile in the United States, and attempted to restart her Facebook presence. This drew the immediate notice of E47, which spurred members to mass report Quynh’s new profiles. Amnesty International, after advocating on Quynh’s behalf, also became a favored E47 target.

Air quality monitoring app AirVisual, based in Los Angeles, announced in October 2019 that it was facing a “coordinated attack” against its reputation after reporting that Hanoi had recently suffered the worst air pollution among 90 major cities, according to Reuters. The day prior, E47 had launched a campaign against the app, according to posts viewed by The Intercept, calling on members to spam the company’s Facebook presence with one-star reviews and fraudulent content violation reports to “pressure the company to issue an apology.”

Further posts reviewed by The Intercept showed E47 administrators organizing attacks against a wide variety of other organizations, including Viet Tan, a pro-democracy advocacy group, and Luat Khoa, an independent news outlet only accessible via Facebook, because it is blocked by the government inside Vietnam. In the August 2019 E47 post announcing the impending Viet Tan attack, one group member noted that the time to strike had come because the organization had lost its blue check verification badge “because the Vietnamese government [supports] FB president Mark Zuckerberg.” Indeed, it can often seem like E47 and Facebook have a terrific working relationship. After E47 mobilized against Luat Khoa’s Facebook presence, specifically targeting posts criticizing “the government or praising human rights activists,” according to one editor, Facebook responded by revoking the paper’s ability to use quick-loading Instant Articles, a feature particularly valuable to users with limited data plans and slow connections in countries like Vietnam. Luat Khoa’s editors say that traffic to their page has fallen by over half since Facebook’s disciplinary measures, and efforts to appeal the decision or plead with Facebook for some understanding were denied and ignored.

Facebook Says Vietnam’s Harassment Team Is Fine

Denial and indifference are the hallmarks of Facebook’s response to E47, according to Mai Khoi and others who have advocated for the company to protect speech on the platform against E47 attacks. Mai Khoi said that her years trying to push Facebook — a company infamous for stalling and dithering unless presented with a high-profile PR crisis — has convinced her that Zuckerberg’s public praise of “free expression” is “a total lie,” a heartwarming line but little more.

“For the last two years, I have been advocating for Facebook to protect the only space where people in Vietnam can express themselves freely,” Mai Khoi said in an interview. “Instead of doing this, Facebook’s policy has been to follow local laws used to silence free speech and allow government troll groups to harass Vietnamese users (online and offline) and censor social media,” adding that “like the Vietnamese government, Facebook is an unaccountable tyranny.”

Mai Khoi said that Facebook has invited her to discuss the threat E47 represents to free expression, and the real-world consequences of Facebook’s inaction, on several different occasions, including multiple conversations with Alex Warofka, a Facebook product policy manager for human rights; Andy O’Connell, head of content distribution and algorithm policy; and Monika Bickert, vice president for global policy management. With each meeting, said Mai Khoi, came another round of reassurances of how sacred Facebook considers the free expression and safety of its users, and how much work the company has put into rooting out bad actors who use Facebook as a civic cudgel in countries around the world. But meeting after meeting, E47 remained online and operational.

Mai Khoi first brought E47’s weaponization of Facebook’s Community Standards to the company’s attention in an October 2018 meeting with O’Connell and Warofka. The company’s early response was encouraging: “I asked them to stop government-supported troll farms from silencing independent journalists and activists on Facebook,” Mai Khoi told The Intercept via email. Facebook quickly provided assurances that it was already tackling the issue of covert state censorship, as well as an offer to work directly with her to make sure it was solved. First among her requests was to establish a dedicated channel between Facebook and Vietnamese civil society groups, in the hope that even if dissidents and journalists had their profiles shuttered or posts removed, they should get an alert and explanation from the company. To her surprise, Facebook claimed that such a channel already existed and that it was in regular contact with the Vietnamese activist community. “This was a big surprise to me,” Mai Khoi said. “I know all the leading independent journalists and activists in Vietnam, and none of them know about any dedicated communication channel between civil society and Facebook.”

In December, Warofka contacted Mai Khoi thanking her for putting E47 on Facebook’s radar, noting that while company privacy policies barred him from sharing any particulars, Facebook would reverse any content deletions or account bans it determined were mistakes as part of an “ongoing investigation.” Warofka signed off by thanking Mai Khoi’s interest in making sure “Facebook remains a place where people in Vietnam and around the world have space to express themselves safely.” Whether Facebook shared this interest was another thing altogether. Mai Khoi replied explaining that while Facebook’s attention to the matter was appreciated, she wondered why E47 and its leaders were still freely using the platform. Mai Khoi received no answer but followed up throughout 2019, asking for an update on Facebook’s investigation into the group and the fates of accounts and pages the group has conspired to take down. “Sorry to send so many emails although accounts of activists and journalists are being locked faster than we can keep track,” she wrote in January 2019. “I hope that in the future we can set up a system so that I do not need to email you every time there is an issue.” This time no one replied.

In June, she tried again: “Do you still work with civil society stakeholders in Vietnam? I ask because there are some recent issues I want to bring to your attention regarding Facebook’s operations in Vietnam although you have not responded to the last few emails I sent.” Finally, Warofka answered, claiming, yet again, that the company was “looking into” unduly locked accounts, but noting that a review of earlier accounts targeted by E47 found that they “were correctly actioned for violations of our global Community Standards.” In other words, Facebook had determined that E47 was using Facebook as designed. The group continued to use content moderation tools to bludgeon dissent as easily as before; the only difference now was that Facebook knew it was happening. “It seems that decisions are being made about access and content in a very arbitrary way with little transparency,” lamented Mai Khoi in a reply to Warofka. “I hope you can find a way to improve this.”

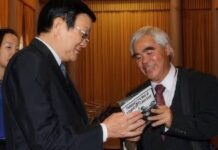

Photo: Vietnam News Agency/AFP via Getty Images

In October, Facebook agreed to another meeting on E47, a move Mai Khoi thought might mean that the company was finally taking the threat seriously. Just that month, according to Human Rights Watch, Vuong, the Vietnamese pro-democracy advocate, was arrested and charged with “making, storing, disseminating or propagandizing information, materials and products that aim to oppose the State of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam” via Facebook. Prior to his arrest, Vuong had been a regular target of E47: “He was an active force in the protests in Ho Chi Minh City yesterday,” read one post reviewed by The Intercept. “I hope you police in the south and in Lac Lam District, Lam Dong province can investigate.” Armed with this and other documented evidence of E47’s efforts, Mai Khoi hoped that this next meeting would be different, an opportunity for Facebook to stop paying lip service to the sanctity of “free expression” and start actually guarding it. Either the systemic gaming of Facebook’s moderation tools was something the company would tolerate, or it wasn’t. With tens of billions of dollars in cash and years of documentation of E47’s conspiring, Facebook could claim neither a lack of resources nor knowledge about what was happening in Vietnam. But what they claimed instead was even more infuriating to Mai Khoi and her allies: E47 simply wasn’t breaking the rules.

The December call, hosted by Warofka, was emblematic of just how feckless Facebook has become, a portrait of an organization that both controls the flow of information to nearly 3 billion people around the world and appears, somehow, unable to address its most flagrant, perennial mistakes and misdeeds. Warofka opened by telling Mai Khoi that he had relayed the information on E47 that she provided to Facebook’s threat intelligence team, responsible for investigations into coordinated inauthentic behavior campaigns, as well as to an internal team tasked with reviewing community standards breaches. The good news ended there. Although Warofka said the company had determined that a small number of Facebook users had violated the site’s rules while trying to silence E47’s targets, he also admitted that “we were not able to uncover activity that meets our definition of coordinated inauthentic behavior based on any of that information.” Although “coordinated inauthentic behavior” has become Facebook’s golden byword in the fight against online disinformation and democratic subversion following the 2016 presidential election, its definition and application remains narrow. So narrow, it appears, that groups like E47 get a pass; their behavior is coordinated, and use of Facebook’s moderation tools maliciously inauthentic, but their overall activity differs sufficiently from the specific 2016 Russian troll playbook to stay on Facebook.

Facebook had determined that E47 was using Facebook as designed. The group continued to bludgeon dissent; now Facebook knew it was happening

“At a high level, we require both widespread coordination, as well as the use of inauthentic accounts and identity,” Warofka told Mai Khoi. Despite the fact that E47 represents the widespread coordination of thousands of Facebook users, many do so under their real names, using their real photos, from “authentic” accounts. By not even bothering to disguise their actions behind false identities, E47 members seem to have yet again found a way to use Facebook’s byzantine rules against the company’s users with total impunity. Even in the face of compelling evidence that E47 works in conjunction with and on behalf of the Vietnamese government — a factor that made Russian attempts at election meddling in 2016 so sensational — Warofka shrugged, explaining that “when we receive a report on our community standards, we do not look at where that report comes from. We don’t care if it’s a government reporting it.”

By Facebook’s own admission, the extremely limited focus on “inauthenticity” meant that flagrant malice, in obvious contravention of the company’s publicly stated values, broke no rules. “It’s actually a very, very narrow range of actors who meet the specific bar of a network of coordinated inauthentic behavior,” Warofka conceded. Facebook had, Mai Khoi learned, specifically investigated E47 and declined to take any action against it: “We were not able to identify a sufficient level of community standards violations in order to remove that particular group or those particular actors.”

In other words, Facebook had determined that spamming bogus reports of porn and imminent violence in the name of suppressing pro-democracy speech was not against its rules.

“When Alex told me that this group doesn’t meet Facebook’s definition of coordinated inauthentic behavior because the accounts were not fake,” Mai Khoi explained to me in a message, “I asked why Facebook doesn’t have a policy banning coordinated authentic behavior — and he had no answer for me.”

E47 Continues To Use Facebook Against Dissidents

Since the 2019 phone call, E47 remains active and undaunted. Vietnamese figures long-tracked and targeted by E47 members continue to wind up imprisoned. In 2020 alone, several longtime E47 targets were arrested on vague charges of propagandizing or violating state secrecy. In October, E47 targets Pham Doan Trang and Nguyen Quang Khai were both arrested by state authorities; Vietnamese human rights advocacy group Defend the Defenders reported that “according to the notice sent to his family dated October 21, the Security Investigation Agency of the Dong Nai province’s Police Department detained Mr. Khai in an urgent case for the act of copying and disseminating state secrets on his Facebook account.”

Both the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and a series of escalating clashes between farmers and government officials over disputed land have become top priorities for E47. In one post reviewed by The Intercept, an E47 member encouraged members of the state security service present in the group to monitor a woman who’d voiced criticism of the government’s coronavirus response. Just 10 days later, she was detained by police, according to the 88 Project, a Vietnamese free speech organization. Another post targeting a man who’d shared a link to Facebook comparing the pandemic responses of Vietnam and Europe encouraged members to beat him to death. As the Los Angeles Times has reported, the fight over land has become a flashpoint in the struggle over criticism of the Vietnamese government on Facebook.

Facebook’s apparent willingness to look the other way while its site is used to punish peaceful political speech has been, to hear people like Mai Khoi and groups like Amnesty tell it, disastrous for free expression and association in Vietnam, a country ranked five places from dead last (above only the likes of China and North Korea) in the Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index.

With the internet dominated by Facebook, traditional media dominated by the state, and the former unwilling to disturb the latter, there’s often simply nowhere left for Vietnamese dissidents to go. The company’s critics in Vietnam and around the world are also running out of options. “We have discussed these things with Facebook over and over,” said Human Rights Watch’s Brad Adams. “They have been willing to talk and their rights people seem sympathetic, but overall the response has been weak, inconsistent, un-transparent, and too ready to compromise basic principles.”

If semi-secretive groups like E47 lose their power to wield Facebook against itself, it may be only because Facebook has recently made it easier to file formal censorship demands. The dirty tricks of E47 could become obsolete if Facebook makes it substantially easier to just ask. “Legal takedown requests have become the recent weapon of choice,” Amnesty’s Ming Yu Hah explained. “Previously, Facebook appears to have resisted such takedown requests where the content was protected by human rights standards governing freedom of expression. However, their announcement of a new Vietnam policy in response to government pressure in April has emboldened the authorities to expand their use of legal takedown requests as an avenue for censorship. According to Hah, Facebook now complies with 95 percent of censorship requests from Vietnamese authorities.

In a sign of just how desperate the situation has become, many Vietnamese dissidents threatened by Facebook’s inaction say that for now, they’d settle for honesty. “Dealing with Facebook is like a walk in the dark for us activists,” said Vi Tran, co-founder of Legal Initiatives for Vietnam, a pro-democracy group. “If Facebook decides to delete a status for any reason, please let us know what is the reason. Giving us the ‘violation of Community Standards’ is not enough because it is arbitrary and vague.”

But after years of disappointment and futility, Mai Khoi, like an increasing number of users in Facebook’s home country, think the time for transparency initiatives and discourse may be over. With huge volumes of advertising and e-commerce cash riding on its continued, unmolested presence in Vietnam, Mai Khoi said Facebook simply can’t be trusted to put its users before its earnings: “Congress needs to regulate and break up the company.”

https://theintercept.com/2020/12/21/facebook-vietnam-censorship/