By Tan Trung Nguyen Quoc

US – Vietnam Review

Editor’s Note: The following text has been adapted to standard American English from Australian English. Footnotes have been removed and minor edits implemented for style and readability.

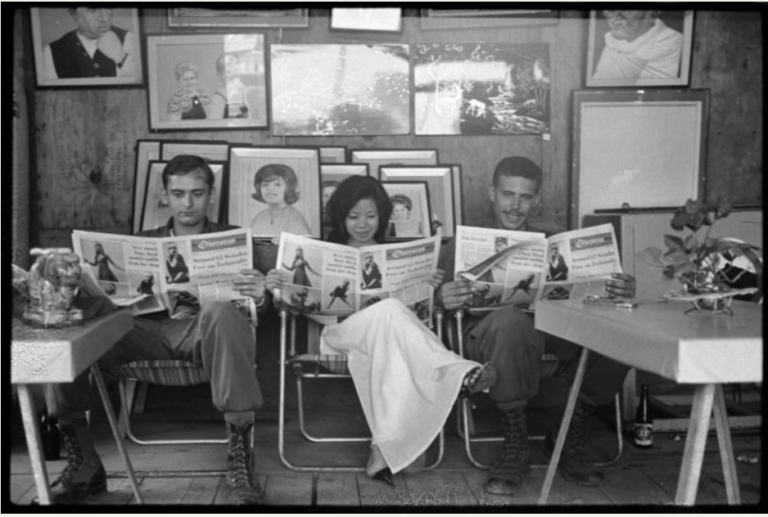

In the fall of 1965, five Vietnamese students travelled to the United States on a State Department tour and pleaded the Republic of Vietnam’s case. It was a nerve-wracking, if not downright terrifying experience for them. At the University of California at Berkeley, the five were booed, and anti-war groups shouted accusations that they were ‘stooges’ of the American and South Vietnamese governments. At other venues, there were refusals even to meet with the delegation. Many Americans believed that those Vietnamese who supported the Saigon government, or opposed Hanoi and the National Liberation Front, were puppets of the American imperial war machine.

Three years later, March 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced that he would not run for re-election. Tired and despondent, he stated:

‘As I sat in my office last evening, waiting to speak, I thought of the many times each week when television brings the war into the American home. No one can say exactly what effect those vivid scenes have on American opinion’ (Ward 2018).

Fast-forward 30 years to 2017, and there was the appearance of a much-praised historical documentary, entitled The Vietnam War. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, the film’s directors, claimed to be challenging misinterpretations of the Vietnam War. It was disappointing, from a historical perspective, that they included in their story the voices of only eight South Vietnamese military veterans and former government officials. The viewpoint adopted in the film was again from the top down, and the effect it produced was to make the Vietnam War seem much the same as other wars in which Americans have been involved during their relatively short 300 years of nation-building. The complexity of Vietnam’s political, military and cultural conflicts during the war was reduced to two basic actors: the Americans, and anyone willing to fight them, yet again.

‘Mediatized history’: history from below?

For better or for worse, news or media or journalism, whichever term is more appropriate in a specific context, has become the favored instrument for the democratization of the past. Those interested in history, whether scholars, politicians, students or citizens, now have to engage with the past in terms of freedom, truthfulness and community. In that sense, history has become the ‘the repository of shared memory’.

Such a development is understandable. For some time now, historical literature has been reminding us of how much of social experience has been left out of history scholarship, which tended to focus on wars, atrocities, the macro-development of social processes and economies.

The complexity, interconnectedness and inaccessibility of most primary historical resources had always ensured that historians and the state apparatus, rather than the wider public, were the official custodians of history. The invention of news media and public journalism appeared to overcome this exclusivity by relinquishing professional control over the gatekeeping and authorship of history.

It is possible to view history-making through media and journalism as an entirely praiseworthy and democratic process that typically begins with the journalist unearthing a story, which is then truthfully told in the face of any danger posed by hostile interests. The story is received by an audience that feels it is being offered an experience at first hand. Journalism becomes the locus at which individuals imagine themselves to be connected, involved, part of the group that celebrates, mourns, suffers or expresses outrage. Prominent British journalist and war correspondent Robert Fisk famously saw journalists as the ‘witnesses of history’:‘I suppose, in the end, we journalists try – or should try – to be the first impartial witnesses of history.”

With that in mind, it is acceptable and reasonable to describe media, and particularly print and television news media, as ‘the first draft of history and also as the first draft of collective memory. Media record events as they happen, presenting us with stories that etch onto our minds the fear, anger, confusion or disgust that often determine our judgments, then stores this information so that it can be accessed by future generations. This is why scholars have had to take note that the lines between academic and popular histories are increasingly blurred. Sir David Cannadine, in the seminal work, ‘History and the Media’, published in 2004, argued that ‘history and the media are more completely interconnected and more variedly intertwined than ever before.’

The phenomenon is inevitable. Apart from compulsory history lessons at school that may inspire a tiny minority to pursue historical studies at a higher level, where else can the rest of us get an understanding of the present and the past? Our entire engagement with history has become mediatized.

However, important as news media are, their qualifications for authorship of the first drafts of history are questionable.

History requires time and context, and there are interdisciplinary aspects that also need to be considered. On the other hand, the information presented by the media is, like memory itself, a physical and mental process unique to the provider and to the receiver. Both memory and journalism are emotive, creative, empathetic, cognitive, selective, and sensory. We edit them, store and share them and rely too much on them without any consideration of widening the perspective or the pool of information. This characteristic often makes it difficult to generalize their relationship with history.

The well-regarded historian and TV film-maker Simon Schama has the perfect description of modern information and communication, which I believe can also provide an explanation of the dangers involved when news and journalistic works are the only forms of historical interpretation the public can access. Schama writes of the ‘chopped-up, speed-driven, flickering restless quality of modern communication’. It is received ‘serially’; our picture of the world is ‘scrambled’, and rhetoric passes ‘through fields of sonic distortion’. In such chaos, history comes to us as a collection of glimpses from the window of a speeding car, each equivalent to one celluloid frame.

Appreciating the source dilemma of global history, as a way to understand a foreign country, or to understand the interconnected history of countries, requires scholars, readers a lot more than the dependence on televised reports and op-eds.

‘It’s a dirty little war.’

The award-winning journalist Dan Rather made the above statement about the Vietnam War on national television, and it has become one of the most quoted and best remembered descriptions of the Vietnam conflict, continuing to shadow the historical remnant of South Vietnam.

The Republic of Vietnam: Media depiction and Historical reality

The Vietnam war is known as the first “television war’. An excerpt from the National Archives History Office, authored by Madie Ward, will serve as a useful first point of reference for understanding how journalism, and its new medium – television, completely changed the way the public accessed and ‘felt’ the war.Ward explained that, in World War II, morale was high and the camera crews of the day naturally stayed in non-combat areas to show the upbeat side of the war. Their stories were broadcast as motion pictures shown in theaters as special events, and no one in their right mind would have wanted to spoil these events with defeatist news. By contrast, the Vietnam War started at a time of easier and greater news coverage.

There are substantial numbers of American scholars who subscribe to the view that televising the Vietnam War helped to divide a nation that had hitherto taken pride in its unity of purpose. Others are not convinced by these accounts of media influence. One could spend a lifetime arguing about the influence of journalism on the outcome of the Vietnam War.

However, within the jungle of blame-shifting and finger-pointing, there is some agreement. The fault of U.S. journalists, according to Arnold R. Isaacs, a war correspondent who has spent most of his career defending the integrity of the news media during the Vietnam War, was that, in reporting the war almost exclusively from the American side, they paid far too little attention to the realities of South Vietnamese people, their hopes and aspirations, their achievements and their losses, and thus they failed in a journalist’s essential mission – telling the story from the ground.

Failure to depict South Vietnam as an essentially democratic nation during its soul- searching struggles

Ngo Dinh Diem was the very model of an elite member of the traditional Vietnamese hierarchy. Rethinking the story of South Vietnam with Diem at its beginning seems to defeat the purposes of this study. But it is also the reason we have to begin the story with him – Diem was the First Republic in the eyes of U.S. news media. And they hated him, professionally.

There is a lot to say about Western news media coverage of Ngo Dinh Diem, and the space and resources of this research will not allow us to deconstruct all of them. Instead, the author will rely on two case studies to encapsulate the false news media depiction of the Diem administration and its representative competence in relation to the people of South Vietnam. First, Diem’s ascendancy to power and, secondly, the Buddhist crisis.

Diem has long been seen as an American lackey, a South Vietnamese puppet of American king-makers. The New York Times described Diem as a man who had ‘turned his back on the world to go into monastic self-imposed exile. He was regarded as lacking the popular appeal of the North’s communist leader, Ho Chi Minh, and his government was depicted as being founded on nepotism and the swift suppression by the secret police of internal criticism. It can be argued that the news media successfully created the conventional wisdom that Ngo Dinh Diem was no more than a pawn of the American anti-communist strategy in Southeast Asia, and that he would do anything he was told to do by his American controllers, as Professor Nu-Ahn Tran has cautiously pointed out. The media depiction of Ngo Dinh Diem’s first republic might lead people to believe that the Republic of Vietnam was from its inception a bad tree that inevitably yielded bad fruit.

Regardless of whether this view was an error made in good faith by the U.S. news media, its historical impact was long-lasting. The news media, in their ignorance of the political context and social complexity of Southern Vietnam, failed to appreciate the grassroots dynamic that led to the rise of Ngo Dinh Diem and his subsequent contribution to the stabilization of South Vietnam.

Unlike the North, with its background of over a thousand years of political practice and its major bureaucratic establishments, South Vietnam – including its capital Saigon – was only 200 years old and could be perceived as a ‘lawless gangland’.

The French colonial administration, notwithstanding the historical rhetoric that, for whatever reason, depicted the French Empire as exercising totalitarian rule in their colonial territories, was never able to achieve control of the village-led communities of South Vietnam. The French relied entirely on local elites to carry out very basic tasks of governance, such as land registration and demographic surveys. The local elites themselves were a loosely self-governing structure that scarcely conformed to the usual characteristics of a bureaucracy. The liberal and anti-statist pattern of the Southerners is confirmed not only by Western records but, more importantly, by local literature and academic evidence.

Trinh Hoai Duc was a prominent mandarin and engineer of southward expansion who served under the Emperor Nguyen Anh. In a work entitled Gia Dinh Thanh Thong Chi (嘉定城通志: The General History of Jiading City), written arguably between 1880 – 1822, he asserted that Gia Dinh and South Vietnam were the lands of migrants, deviants, vagabonds, fugitives and refugees.

Due to the agricultural fertility of the land and its rich diversity of species, the aspiration of the inhabitants was not towards politics and law and order, but towards heroism, adventurism, personal freedom and entrepreneurship. Living alongside Western settlers and traders, Cambodians, Chams, Chinese and many more, the population of Gia Dinh defied the Confucian traditions and practices of the north. Creating their own ‘lễ” (ceremony) and ‘tục’ (custom), and modifying their Vietnamese language and mixing their heritage, they were able to establish the most vibrant and prosperous region of Vietnam.

Through the eyes of Son Nam, a notable writer on the Southward Reclamation (‘Khẩn Hoang miền Nam’), Gia Dinh society seemed to resemble the ‘Wild West’ era of westward expansion in the United States, which was happening at the same time (i.e., the early 19th century). For instance, in ‘Huong Rung Ca Mau’ (The Forest Scent of Ca Mau), Son Nam tells the stories of individuals who enjoyed their freedom deeply isolated within nature. We meet Tu Thong, an old man living alone in Co Tron Ait, who had never seen or heard of French officials and their colonial administration in Vietnam, who regarded the modern and powerful ‘ca – nô’ (Canot in French, motorboat in English) as nothing more than ‘a duck egg shell in the sea’, and who felt that leaving his ait would deprive him of all his freedom.

For all their poetic libertarianism, these stories are evidence of a region that was not prepared for formal politics and the imposition of a thoroughgoing system of bureaucracy. This deficiency, in the analysis of Dennis J Duncanson, has favored the formation for mutual succor of cliques, sects, and half-secret societies, boasting supernatural or ideological sanction. The rise of the Binh Xuyen gang, and then the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao religious militias, and the unexpected rise in influence of major religions such as Buddhism and Christianity after the mayhem of World War II, turned South Vietnam into a ticking bomb liable to be detonated by any discussion of statehood and unity.

The massacres, executions and assassinations carried out by the Viet Minh (Việt Nam Độc lập Đồng minh hội – or Vietnam Independent Alliances, an alter ego of the Vietnam Communist Party), only added fuel to the fire.

The establishment by the Viet Minh in 1945 of the so-called ‘Democratic Republic of Vietnam’, largely seen in the West as the first independent government representing the entirety of Vietnam after French colonial rule, was ill-received in southern Vietnam.

Every faction there has a different name for this period.

Trotskyist communists in Vietnam and in the rest of the world called the period from 1945 to 1950 the ‘Stalinist Massacre’ since the Vietminh kidnapped and executed the majority of the Trotskyist leaders and subsequently many of their followers. With the killing of most of its brightest members, including Ta Thu Thau, Hinh Thai Thong, Tran Van Thach, Tran Dinh Minh, this once-influential movement in Southern Vietnam was eliminated.

Religious history, desperately safeguarded by groups such as Hoa Hao, also depicts the Viet Minh and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in a very different manner. The massacre of hundreds of Hoa Hao followers by the Viet Minh in Can Tho in 1945 strengthened their opposition to communist rhetoric. After 1947, when Huynh Phu So – the Virtuous Master of Hoa Hao – was ambushed and killed by the Viet Minh, his group of almost one million farmers and commoners turned into an anti-communist as well as an anti-French movement. In Quang Ngai 1945, many adherents of Cao Dai – another prominent local religion with millions of members – were also attacked and killed by the Viet Minh. A large number of other Southern political leaders and intellectuals were killed by the Viet Minh after 1945, including Pham Quynh, Ngo Dinh Khoi (Ngo Dinh Diem’s brother) …

The situation described above created a unique political situation in Southern Vietnam, with different factions running their own militias, either for security reasons or in the interests of organized crime. Although the conditions inevitably gave rise to an anti-communist nationalist movement, the will to unite under a single banner was absent.

It is through an awareness of this complexity, rather than through a bland assumption reliant on heavily mediatized resources that Ngo Dinh Diem was purely an American choice, that we can begin to understand the apparent suddenness with which he came to be considered the man for the job, the reasons for his invitation by the Bao Dai Emperor and why his return to Vietnam was welcomed by most grassroots organizations in Southern Vietnam. The South desperately needed a prestigious political icon, and Ngo Dinh Diem, who was opposed both to the Communists and the colonial administration, who had survived the bloodshed after 1945 and who had experience of government, was a rational choice.

What then should we say on the subject of freedom in the South? Was not Diem responsible for the curtailment of personal freedom? Didn’t he suppress all dissidents and establish totalitarian control over Southern society? Such were the canards recurrently found in U.S. media from 1960 onwards.

This is odd, given the fact that the so-called all-powerful ‘secret police’ of Diem’s administration never had a significant presence outside of Saigon. Official documents housed at the National Archives Centre II in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon), and several Western historical resources clearly show that Diem, in pursuit of pacification and community self-determination, had never even formed a rural police force for fear of interfering with the people’s traditional way of life (Duncanson 1967).

The question of whether this was a sensible decision from the standpoint of the safety and welfare of the populace in view of the constant acts of terror carried out by the National Liberation Front (NFL) is beyond the scope of the present discussion. Yet, suffice to say that it is misleading to depict the First Republic as an entirely authoritarian regime.

Another recently published collection of essays written by well-known Vietnamese authors between 1954 and 1975 (“Bàn về Giáo dục Việt Nam trước và sau 1975” (On Vietnam Education before and after 1975), edited by Tran Van Chanh), sheds light on the academic and political freedom, freedom of association and status of civil rights in South Vietnam. Diem and the officials of the First Republic could be considered as the people who laid the foundation stones of that freedom. The book is a record of the discussions and critiques of scholars living in the era and it enables us to obtain an accurate picture of the South and its vivid market of ideas. Private organizations and entities were encouraged to establish private schools and build their own educational programs, communism could be introduced and taught in schools and it was easy for journals and newspapers to start up. The South, unlike the North, was a place where academic discussions and political debates on national identity, state development, and spiritual enquiry and religious pluralism could flourish.

However, all this was followed by the Buddhist Crisis, the downfall of Ngo Dinh Diem, and the ‘Western-mediatized’ history, which had a detrimental effect on the legitimacy of the First Republic and its successor.

The Buddhist Crisis began on 8 May 1963, when a dispute of religious flag displayed led to a political turmoil. Diem agreed to meet with the Buddhist leadership and promised financial aid for the death victims’ families. He insisted, however, that there was no religious persecution in South Vietnam, and that the assault was a communist-orchestrated. This view was not accepted by the major sects of Buddhism in South Vietnam. As June approached, the Buddhist Crisis was spinning ‘out of control’. 11 June 1963, seventy-three-year-old monk Thich Quang Duc sat down at the intersection of Saigon’s major boulevards and consigned himself to death by fire.

The media effectiveness of the self-immolation was undeniable. Quang Duc’s suicide called attention to the situation of Buddhists in South Vietnam, and their protests appealed to the most cherished American value: freedom of religion.

Marguerite Higgins, a prominent correspondent in the Saigon press corps, assumed that it was Diem’s intention to discriminate and even to kill Buddhist supporters: ‘What was President Ngo Dinh Diem doing to cause these Buddhists to choose such a horrible death as self-immolation?’

The New York Times, a major anti-war news outlet, spent a full-page advertisement in which twelve American clergymen opposed the First Republic, insisting on ‘the fiction that this is ‘fighting for freedom’

All the news dispatches coming out of Saigon estimated that the Buddhists constituted 70 or even 90 per cent of the national population. Lack of faith in the First Republic manifested itself when Diem’s government began to be seen as a discriminative Christian minority regime disconnected from the Buddhist ‘majority’.

The New York Times speculated that ‘the crisis is worth about 15 major battlefield victories to the Communists.’ and its reporter David Halberstam confidently asserted that ‘the United States backed the wrong man. Their editorial of 17 June reflected these assumptions and speculations, and even hinted at the need to overthrow Diem: ‘If he cannot genuinely represent a majority then he is not the man to be President.’

Time magazine, in a very under-researched manner, explained that ‘Buddhist discontent could cause passive resistance to government programs in the rural provinces where political unity is the key to victory in the war against the Communist Viet Cong.’

This ‘first draft of history’ put forth by reporters had a significant influence on public opinion. According to the researcher Zi Jun Toong, Diem’s fall from grace in international opinion played a vital role in Washington’s decision to support a coup to overthrow the Diem government. However, if one digs deep enough, the media assertions can be seen to conflict with the historical record.

First of all, assessments of the degree of discontent in the country were highly inaccurate. In a little-known but well-conducted study of Buddhism in Vietnam, it was reported that only 30 percent of South Vietnamese were actually practicing Buddhists. The sect that was directly in dispute with the First Republic, the General Association of Buddhism, was even smaller in size. It represented only six of South Vietnam’s sixteen Mahayana sects, which comprised some 3000 monks, 600 nuns and around 70,000 to 90,000 members of youth groups.

These facts found accurate expression in General Victor Krulak’s report cited below, although it seems to have been lost in the morass of sensational headlines and Cold War dualism:

‘The religious aspect of the issue has a narrower base than public reports might suggest. There is a tendency to classify all non-Christians as Buddhists. In fact, many are simple ancestor worshippers in the Chinese tradition, while other major religions are also represented in the count…’

Secondly, there was misapprehension concerning the Buddhist Crisis.

CIA rejected the view that there was formal suppression of religious freedom in South Vietnam, although it did affirm that Diem’s government had successfully curbed the political influence of some religious groups (specifically Hoa Hao and Cao Dai). Also, a United Nations independent fact-finding team concluded that the First Republic had not systematically oppressed the Buddhists. Fernando Volio Jimenez, Costa Rican ambassador to the UN and a member of the team, told the NC News Service:

‘There was no policy of discrimination, oppression or persecution against the Buddhists on the basis of religion. Testimony to this effect was usually hearsay, and was expressed in vague and general terms.’

It is also vital to remember that, it was under Diem’s First Republic (from 1956 to 1962), Vietnamese Buddhism flourished and the membership of Buddhist associations increased dramatically, in contrast to what was happening in the Communist North at the same time, where religious persecution rooted out Christianity and Taoism, as well as Buddhism, from the land of ‘a thousand-year-old civilization’. My informal interviews with Buddhists and Catholic refugees living in exile in the U.S. support the view that there was no discriminatory policy that excluded Buddhists from political and social activities in the First Republic (and indeed the Second Republic). Some interviewees emphasize the fact that many Buddhists obtained major roles in the army of the Republic of Vietnam.

After 1975, the Southern population soon came to understand what ‘religious suppression’ really meant. Thich Tri Quang, who had been an internationally-recognized figure during the Buddhist Crisis, was arrested under the revolutionary regime and kept under house arrest for decades, an event that attracted absolutely no attention from the U.S. news media. Nguyen Thanh Nam, the founder of the Religion of Harmony (Hòa đồng Tôn giáo) known as the ‘Coconut Religion,’ was killed in a skirmish between his supporters and the forces of the revolution. He had previously been hailed by the US press as a hero of the anti-war movement (Steinbeck 2019).

The intention here is not to canonize Ngo Dinh Diem as the North has canonized Ho Chi Minh. Yet, it does intend to show how under-researched and misleading U.S. news media coverage has been and how it has affected the collective memory, and ultimately the narratives, that constitute the history of the Republic of Vietnam – the very first endemic Vietnamese liberal democracy.

The failure to depict a comprehensive picture of the warring factions: war crimes and forgotten terrorism

Asked to recall their most vividly remembered televised images of the Vietnam War, most people would include the one of General Loan executing a Viet Cong officer during the Têt offensive. And to many, the supreme example of the malevolence of American and Southern Vietnam troops was the My Lai massacre, where hundreds of civilians were killed by the forces that were supposed to protect them. These two incidents, more than any others, have been used to exemplify the illegitimacy of the southern Republic of Vietnam and of US involvement in the war. Concentration by the news media on a particular incident or image can alter the course of debates on the war. And the news media are very aware of their power in this respect.

Almost 50 years after the war, the Washington Post still hails the picture of General Loan of the ARV extrajudicially executing Bay Lop, the Vietcong insurgent (a Vietnamese term for NFL members) – as a crucial milestone that changed the tide of public opinion and ‘helped end the war’. Christian G. Appy, professor of history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, contended that this picture alone ‘introduced a set of moral questions that would increasingly shape debate about the Vietnam War: Is our presence in Vietnam legitimate or just, and are we conducting the war in a way that is moral?’

More problematically still, the inner circle of the media network offered journalists many opportunities to tell the public that supporting South Vietnam was morally wrong, while maintaining silence on the many other reasons for explaining why it was the opposite.

Seymour Hersh who became famous for his investigative report on the My Lai massacre, and his article earned him a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1970. The widespread publicity given to the My Lai incident had ramifications that went beyond mere dissemination of a news event. Disturbingly, in a Gallup/Newsweek opinion poll intended to discover whether or not the public regarded the My Lai massacre as an isolated event, 52 percent of the interviewees stated the belief that, on the contrary, it was a common one.

The author recognizes that the journalists of that era pursued some noble causes. However, it is also contended that journalists were to blame for the distorted public view on who was responsible for the blurry line between ‘combatant’ and ‘non-combatant’ in the Vietnam War, and who was responsible for the normalization of war and death in the daily lives of South Vietnamese civilians. In the interests of fairness, and not to exonerate General Loan and US troops from any unlawful conduct on their part, it should be stated that the Tet Offensive was also an example of the diabolical cruelty and destruction wrought by the NLF and their communist partners in South Vietnam. These realities are all too often ignored by the ‘first drafters of history’.

The ‘chopped-up, speed-driven, flickering, restless quality’ of the news media’s depiction of the Vietnam War was not only inaccurate but unethical, especially since historians specializing in the actual political affiliations and grassroots issues in the South are unanimously agreed that the North and its proxies constantly engaged in terrorist activities during the period.

An article by Dr Robert G. Scigliano, entitled ‘Political Parties in South Vietnam under the Republic’ describes the varieties of terrorist acts carried out in the Republic of Vietnam from its very inception. There were anonymous death threats by mail, abductions of family members and assassinations of local officials, village chiefs and local influencers such as teachers.

Normal activities of the South Vietnamese government and welfare-oriented programs, such as demographic surveys, land reform and even go-to-school encouragement programs for children in rural areas were also affected by Vietminh and later the NLF. Participation in any of these campaigns was liable to result in death for innocent civil servants, social workers and local leaders who tried to motivate others to take part. Even more disturbingly, it is estimated that, between 1955 and 1959, on average one civil servant was killed by the communist rebels every day.

The reality is confirmed in the Saigon Daily News Round-up reported by the United States Operation Missions, an important archival resource for understanding the daily lives of the Southern Vietnamese, and one that is rarely used in the existing literature. It is only necessary to read through a few daily bulletins to understand the pattern. For example, Newsletter no. 166, dated July 27, 1956, reported that a 65-year-old landowner named Vo Van Meo was beheaded by the Vietcong in Can Tho, and that a police officer in Soc Trang was killed by the Viet Cong while on patrol.

In a ‘Vietnam Information Note’ prepared by the Office of Media Services, Bureau of Foreign Affairs, Department of States, completed in 1967, there is a list of further examples of the NFL’s non-selective terrorism.

In 1962, two social workers employed in a national dengue control project, Phan Van Hai and Nguyen Van Thach, were slashed to death in Bien Hoa. To the southwest, in Can Tho, the Viet Cong was responsible for throwing a grenade into a crowded theatre, killing 108 people, including 24 women and children.

In 1964, the Kinh Do Cinema in Saigon was bombed, killing 32 Vietnamese people and 3 Americans.etc.

Although such a brief bullet-point description of the terrorism inflicted on the Southern population is an inadequate means of paying respect to the thousands of victims, it will serve to illustrate the fact that the communists exposed South Vietnam to constant, open-ended, faceless warfare, at the expense of every single international principle of humanitarian law. It is also the best way to explain why it was that the population of the South was the first to become exhausted by the war, rather than the population of the North, which faced the more conventional forms of warfare waged by the Americans and the Republic of Vietnam.

Professor Douglas Pike of Texas Tech University, a leading American historian and foremost scholar on the Vietnam War and the Viet Cong, has illustrated the deliberate nature of communist terrorism in South Vietnam. These were not random incidents or the impulsive actions of individual fighters. Rather, as Pike puts it, the so-called freedom fighters of the NLF turned into ‘full-time terrorists.’ In his encyclopaedic work, ‘The Viet Cong Strategy of Terror’, Pike obtained important evidence, derived from primary sources of the NLF’s horrific conduct (Pike 1970).

In an attempt to justify the killing of civilians in rural area and villages in South Vietnam, on 28 September 1965, the Nhan Dan newspapers (the official mouthpiece of the Communist Party), quoted the NLF leaders as follows:

“We never did it without reason. We advised people who cooperated with the government to stop. Some of them were very stubborn. We would warn them three times, but still some refused to leave the government side… So they deserved to be punished (killed)”.

As if it were not disturbing enough to kill civilians because of their political affiliation, the following explanation was given for the killing of social welfare workers:

“The enemy is concentrating its greatest efforts against the countryside. It is trumpeting about the vanguard role of the so-called Revolutionary Development groups. These are people who are given a quick training course to turn them into hunting dogs to operate under the cover of cultural, educational and social welfare work, using intimidation and demagogy… We are attacking and punishing these cadres right in their dens…”

This aspect of the war inspired Professor Anthony James Joes of Saint Joseph University to devote a chapter of his work on guerrilla war and its political consequences to an examination of the brutality of the Viet-cong terrorist campaign and its consequences.

He found that the communist forces killed corrupt civil servants to gain popularity; but they also killed honest and diligent community leaders and teachers to convey the message that the Saigon government would not be able to protect everyone. They simultaneously destroyed the capacity for local government, leaving communities fearful and leaderless.

Professor Joes identified teachers as among the most common targets. This was because they were usually nationalist in their sympathies, knowledgeable, mistrustful of communism and often had a certain influence on their communities. Joes noted that, as of 1965, as many as 25,000 thousand civil service workers, teachers, village chiefs and civilians had been killed by the Viet Cong. It was a strategy that completely deprived South Vietnamese local communities of their capacity for leadership, vitality and resilience.

***

“‘It’s a dirty little war.’

The Vietnam war was a vigorously debated global event. And historians who seek connections across space and chronologies, combining local and global perspectives, will need to go beyond the grand, yet short and opinionated narratives that are often produced by the news media. And with the dissemination and acceptance of the “news” cited above, true history lost its voice. The blurred line between media, collective memory and history resulted in a reprehensible crime against history itself.

On the other hand, the claims of journalism must be taken seriously. ‘Historic’ ‘epoch-making’ ‘earth-shattering’ reports and images do indeed play a paramount role in shaping collective memory. However, if history is not to be reduced to a collection of headlines, journalism needs to transcend the ‘emotive, empathetic, cognitive, selective and sensory’ elements that were responsible for the ‘sonic distortion’ in its coverage of the Vietnam War.

Works Cited:

Astor, Maggie. 2018. “A Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War.” The New York Times Feb. 01 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/world/asia/vietnam-execution-photo.html

BBC. 2019. “Vietnam country profile” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-16567315 \

Best, Kenneth. 2020. UConn Historian: South Vietnam Archives Provide New Insights into War May 5, 2020. https://today.uconn.edu/2020/05/uconn-historian-south-vietnam-archives-provide-new-insights-war/

Biesecker, B. 2002. “Remembering World War II: The Rhetoric and Politics of National Commemoration at the Turn of the 21st Century.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 80 (4): 393–409.

Bigart, Homer. 1963. “War Against Reds Dominated News.” New York Times, August 22 1963, p. 3.

Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 2001. “Vietnam: The Hoa Hao religion: type, structure, leaders, number of members, and the treatment of members by the government.” 23 May 2001, https://www.refworld.org/docid/3df4bec514.html [accessed 5 December 2020]

Cannadine, David. ed. 2004. History and the Media. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 2

Cao Đài Đại Đạo. “Tiểu sử Đức Huỳnh Phú Sổ”. https://sites.google.com/site/thienchaucom/–tieu-su-dhuc-huynh-phu-so

Choi, S. 2008. “‘Silencing Survivors’ Narratives: Why Are We Again Forgetting the No Gun Ri Story?” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 11(3): 367–88.

CIA. 1963. Special Report: The Buddhists in South Vietnam. https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP79-00927A004100030002-4.pdf

Daily News from New York. 1963. “Rusk condemn Diem in newmen assault” Sunday, October 6, 1963 https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/459991961/

Duncanson, Dennis. J. 1967. “Pacification and Democracy in South Vietnam.” The World Today 23, no. 10: 410-418 Published by: Royal Institute of International Affairs. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40393927

Fisk, Robert. 2005. The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East. New York: Knopf.

Garde-Hansen, Joanne. 2011. Media and Memory. Edinburgh University Press.

Hadyniak, Kyle. 2015. “How Journalism Influenced American Public Opinion During the Vietnam War: A Case Study of the Battle of Ap Bac, The Gulf of Tonkin Incident, The Tet Offensive, and the My Lai Massacre.” Honors College,222. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/222

Halberstam, David. 1963. “Religious Dispute Stirs South Vietnam: Buddhist Struggle Poses Major Threat to Diem Rule and the War Effort Against the Vietcong”, New York Times, June 16 1963, IV, p. 6.

Halberstam, David. 1965. The Making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam During the Kennedy Era. (New York: Alfred Knopf,)

Hersh, Seymour. 1969. “The My Lai Massacre.” St Louis Post-Dispatch, November 20 1969.

Higgins, Marguerite. 1965. Our Vietnam Nightmare. Harper & Row Publishers. p. 4.

Huyssen, Andreas. 2003. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of. Memory. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Isaacs, Arnold R. 2017. “Facts About the Vietnam War, Part IV: U.S. Journalists Didn’t Lose the War, Celebrate the Enemy, or Vilify American Soldiers.” War on the Rocks, September 15, 2017. https://warontherocks.com/2017/09/facts-about-the-vietnam-war-part-iv-u-s-journalists-didnt-lose-the-war-celebrate-the-enemy-or-vilify-american-soldiers/

Jacobs, Seth. 2004. America’s Miracle Man: Ngo Dinh Diem, Religion, Race and U.S. Intervention in Southeast Asia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Joes, A. James. 2001. The War for South Viet Nam: 1954 – 1975. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Kitch, C. 2008. “Placing journalism inside memory – and memory studies.” Memory Studies, 1(3): 311–320.

Krulak, Victor. 1963. “Report by the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Special Assistant for Counterinsurgency and Special Activities” in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume III, Vietnam, January–August 1963 / https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v03/d207

Michigan State University. 1958. 3 Years of Achievements of President Ngo Dinh Diem Administration, http://vietnamproject.archives.msu.edu/fullrecord.php?kid=6-20-1CF

New York Times. 1963. “We, Too, Protest” (Full-page advertisement). New York Times, June 27 1963.

Pike, Douglas. 1970. The Viet-Cong Strategy of Terrorhttps://www.awm.gov.au/collection/LIB44298

Prados, John. 1995. The hidden history of the Vietnam War. I.R. Dee Chicago

Robinson, S. 2006. “Vietnam and Iraq: Memory versus History during the 2004 Presidential Campaign Coverage”, Journalism Studies 7(5): 729–44.

Ruane, Michael E. 2018. “A grisly photo of a Saigon execution 50 years ago shocked the world and helped end the war.” The Washington Post February 01 2018.

Schama, Simon. 2004 “Television and the Trouble with History” in Cannadine, David. ed. History and the Media. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 23

Scheer, Robert. 1995. “Covert action: The 40-year contest to outdo the KGB would be laughable but for the impact it left all around the globe.” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 7, 1995 https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-11-07-me-133-story.html

Scigliano, Robert G. 1960. “Political Parties in South Vietnam Under the Republic.” Pacific Affairs 33, no. 4: 327-46. doi:10.2307/2753393.

Steinbeck, John. IV. 2019. “The Coconut Monk.” The Buddhist Review, Spring 2019. https://tricycle.org/magazine/coconut-monk/

Stur, Heather. 2018. “Fateful Misunderstandings about the Republic of Vietnam.” Diplomatic History, 42, no. 3 (June): 390–395

Sơn, Nam. 1962. Hương rừng Cà Mau. Phù Sa Publisher.

Texas Tech University. The Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive. The Tet Offensive (Tết Mậu Thân) https://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/exhibits/Tet68/hue5.php

The New York Times. 1961. “Tenacious Vietnamese; Ngo Dinh Diem.” May 13, 1961. https://www.nytimes.com/1961/05/13/archives/tenacious-vietnamese-ngo-dinh-diem.html

The Office of Media Services, Bureau of Foreign Affairs, Department of States. 1967. “Vietcong Terror Tactics in South Vietnam.” https://books.google.co.th/books?id=d_pAwTLh1A8C&pg=PP2&lpg=PP2&dq=THE+TRUTH+OF+VIET+CONG+TERROR&source=bl&ots=VdBgc0dkoN&sig=ACfU3U1Dr2Q3MmC1uoEa4eX8EzcexkluLA&hl=en&ppis=_c&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=THE%20TRUTH%20OF%20VIET%20CONG%20TERROR&f=false

Time. 1963. “South Vietnam: Trial by Fire.” Time, 21 June 1963. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/0,9263,7601630621,00.html

Toong, Z. Jun. 2008. “Overthrown by the Press: The US’s media role in the Fall of Diem.” Australasian Journal of American Studies 27, no. 1: 56-72, 57

Tran., Nu-Anh. 2013. Contested Identities: Nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1954-1963). University of California, Berkeley https://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/etd/ucb/text/Tran_berkeley_0028E_13291.pdf

Trần, P. 2020. “Cuộc phiêu lưu của ông Đạo Dừa giữa lằn ranh tôn giáo và chính trị.” Luật Khoa tạp chí, February 09 2020. https://www.luatkhoa.org/2020/02/cuoc-phieu-luu-cua-ong-dao-dua-giua-lan-ranh-ton-giao-va-chinh-tri/

Trần, P. 2020. “Cuộc đời chìm nổi của ba nhà sư: Thích Nhất Hạnh, Thích Trí Quang và Thích Quảng Độ.” Luật Khoa tạp chí, April 12 2020. https://www.luatkhoa.org/2020/04/cuoc-doi-chim-noi-cua-ba-nha-su-thich-nhat-hanh-thich-tri-quang-va-thich-quang-do/

Trần, V. Chánh. 2020. Bàn về Giáo dục miền Nam Việt Nam trước và sau 1975. Omega Publisher

Trịnh, H. Đức., Phạm, H. Quân. (Translator) 2019. Gia Định thành Thông chí. Nhà xuất bản tổng hợp Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh.

United States Operations Mission. 1956. “Saigon Daily News Round-Up, No. 166.” July 27 1956 http://vietnamproject.archives.msu.edu/fullrecord.php?kid=6-20-1B50

Vũ, N. Chiêu. 2017. “Hòa Hảo.” Nghiên Cứu Lịch Sử. https://nghiencuulichsu.com/2017/10/10/hoa-hao/

Ward, Madie. 2018. “Vietnam: The First Television War.” National Archive (blog), January 25, 2018. https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2018/01/25/vietnam-the-first-television-war/

Zizzamia, Alba. 1963. “Un Investigator explains Vietnam findings.” The Monitor, Volume CV, Number 39, December 27 1963. –https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=tmon19631227-01.2.17