Assaults on Bloggers and Democracy Campaigners in Vietnam

Summary

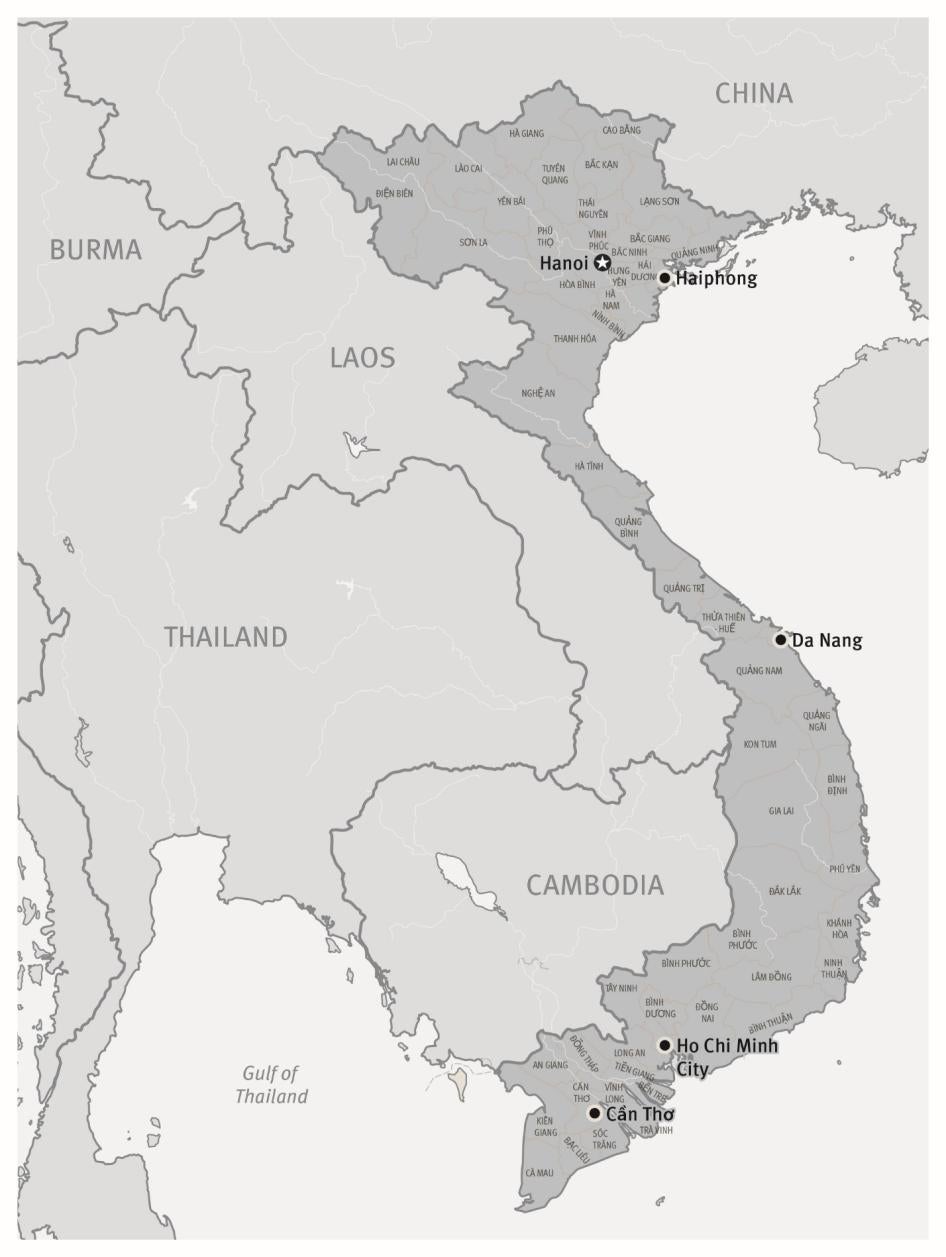

In celebration of International Human Rights Day, on the morning of December 6, 2015, the prominent lawyer and human rights activist Nguyen Van Dai delivered a talk at Van Loc parish in Nam Dan district, Nghe An province, about the rights enshrined in Vietnam’s Constitution. That afternoon, he left for Hanoi, accompanied by fellow activists Ly Quang Son, Vu Van Minh (also known as Vu Duc Minh), and Le Manh Thang. During the course of the journey, their taxi was forcibly stopped by a group of roughly a dozen men wearing civilian clothing and disguised by surgical masks. Nguyen Van Dai says the men dragged them out of the taxi, beating them with wooden sticks on their thighs and shoulders, and forced him into their car. The beating continued inside the car:

They slapped me on my face continuously, and hit me on my ears and my mouth. Once the car arrived at Cua Lo beach, they stripped me of my jacket and shoes, pushed me out onto the beach and left.

The three other rights activists were also severely beaten. According to Ly Quang Son:

The thugs dragged Vu Van Minh out [of the car] and hit him repeatedly in the legs with a stick.… They also dragged Thang out of the car, hitting him in the chest with a stick. Minh tried to hold on to Thang and I tried to grab their sticks. Then another thug whipped me on my hand and I had to release the stick. I used my feet to kick them about the face and head, but they struck me on my ankles, shins, and calves. Minh was unable to hold on to Thang.

Ly Quang Son reported that the men drove Le Manh Thang away in a car to an unknown location, took his cell phone and wallet, and abandoned him by the side of the road. During the trip, the men punched Thang repeatedly in his face and body. According to Nguyen Van Dai and Ly Quang Son, the taxi driver was also beaten by the men.

The December 6 incident was not the first time Nguyen Van Dai had been attacked in this way. In May 2014, while in a café in Hanoi along with several rights activists, a group of men appeared, threw a glass at him, and beat him. In January and March 2015, groups of men attacked his house and tried to break down the door.

***

The attacks on Nguyen Van Dai and his colleagues illustrate a disturbing trend in Vietnam: physical assaults on activists by groups of men who appear to act at the direction of or with the acquiescence of officials. To date, most authoritative assessments of human rights conditions in Vietnam have relied on measures of formal judicial repression (data on arrests, trials, convictions, and sentences imposed by Communist Party-controlled courts or officials acting in their formal capacities), and give too little attention to the frequency and significance of the kind of attacks documented here, effectively a form of extra-judicial repression.

This report attempts to fill in the gap, documenting 36 recent cases in which human rights activists were beaten by “thugs” in Vietnam. All the accounts are based on online sources, including eyewitness accounts of assaults posted on Vietnamese-language blogs and social media, often with photographic evidence, as well as on foreign media accounts, cross-checked against other independent accounts of the same incidents wherever possible.

All the assaults documented here took place between January 2015 and April 2017. In many cases, the assaults took place in plain view of uniformed police officers who did not intervene. Some of the beatings took place in the presence of uniformed officers within the confines of a police station. In many of the cases, the assaults took place in tandem with and seemingly in support of official repressive measures against the activists in question. In almost all the cases, the activists targeted by “thugs” were also targeted for arrest and other forms of official repression.

While the precise links between the thugs and the government are usually impossible to pin down, in a tightly controlled police state there is little or no doubt that they are aligned with and serving at the behest of state security services.

Physical attacks against human rights activists and bloggers in Vietnam are not a new phenomenon. For example, upon returning to Vietnam in December 2005 from a trip to the United States for medical treatment, the late dissident Hoang Minh Chinh and his family were set upon by a mob of about 50 people. The mob cursed Hoang Minh Chinh for publicly criticizing rights violations in Vietnam while he was overseas. They used wooden sticks to break down the door and to smash the windows of his home; threw rotten shrimp paste, tomatoes, and eggs into his house; and kicked and hit members of his family. The family called the police; police officers came but simply witnessed the attack, doing nothing to stop it.

Other prominent rights bloggers and activists have suffered physical assault prior to the period covered by this report, including prominent former political prisoners Huynh Ngoc Tuan, Le Quoc Quan, Truong Minh Duc, Nguyen Bac Truyen, Pham Ba Hai, Bui Thi Minh Hang, Pham Thanh Nghien, Do Thi Minh Hanh and Le Thi Cong Nhan, and activists Nguyen Hoang Vi, Le Quoc Quyet, Duong Thi Tan, Ngo Duy Quyen, Pham Le Vuong Cac, Huynh Thuc Vy, and many others.

Information about these kinds of attacks is incomplete because of limitations on access to Vietnam and censorship of the media. Human Rights Watch research has found that in 2013, Vietnam convicted at least 65 rights activists and bloggers and sentenced them collectively to several hundred years in prison. During that same year, according to a report issued by the Association of Former Prisoners of Conscience (Hoi Cuu Tu nhan Luong tam), at least 18 physical attacks were carried out against 71 rights campaigners.

In 2014, during an especially contentious phase of negotiations over the Trans-Pacific Partnership between Vietnam and the United States, the number of people convicted for political crimes in Vietnam decreased to 31. However, according to the Association of Former Prisoners of Conscience, the number of physical attacks increased to at least 31 incidents targeting 135 rights bloggers and activists.

In 2015, the number of reported convictions continued to decrease, with only seven activists convicted throughout the year. On the other hand, according to research by Human Rights Watch, roughly 50 bloggers and activists reported that they were assaulted in 20 separate incidents. In 2016, at least 21 rights campaigners were convicted while at least 20 physical assaults were carried out against more than 50 people.

Physical attacks against rights campaigners usually take place in four different situations. The first is an attack against a single individual, either at home or on the street. Examples include attacks against Father Nguyen Van The in May 2016, Nguyen Van Thanh in June 2016, La Viet Dung in July 2016, and Nguyen Trung Ton in February 2017.

A second situation is when a group of rights activists suffers an attack, often for carrying out acts in support of fellow activists, such as visiting a recently released political prisoner or attending a wedding of a rights campaigner. Examples of these attacks include assaults against visitors of political prisoners Tran Anh Kim in January 2015 and Tran Minh Nhat in August 2015.

A third situation involves attacks against activists for participating in public events such as pro-environment protests, or demonstrations outside local police stations demanding the release of fellow activists.

A fourth context is inside police stations, as with the reported beatings of Tran Thi Hong and Truong Minh Tam in April 2016 while they were being detained for interrogation.

In many incidents, assailants are reported to have worn surgical masks. In some cases, as noted above, activists report that uniformed police were present, but did nothing to stop the attack. In almost all cases, no one is held responsible for the attacks. Many activists have made reports to the police about the attacks, but few if any investigations seem to have been carried out; Human Rights Watch is aware of only one case in which the attackers and local police leaders alleged to be responsible for the assault were investigated.

Despite great risks to their personal safety and freedom, the community of rights bloggers and activists continues to grow bigger and stronger in Vietnam. Aided by the internet, particularly social networks such as Facebook and YouTube, rights campaigners increasingly are in contact and support one another in their struggles for political freedom and basic rights.

Numerous rights groups have been founded within the last five years, including the pro-democracy No-U Football Club, the Association of Gourd and Squash Mutual Assistance (Hoi Bau bi Tuong than), Vietnamese Women for Human Rights (Hoi Phu nu Nhan quyen Viet Nam), the Independent Journalists Association of Vietnam (Hoi Nha bao Doc lap Viet Nam), Former Vietnamese Prisoners of Conscience (Hoi Cuu Tu nhan Luong tam Viet Nam), the Brotherhood for Democracy (Hoi Anh em Dan chu), and the Association for Support of Victims of Torture (Hoi Ho tro Nan nhan Bao hanh).

In addition to carrying out traditional rights activities such as staging peaceful protests, publishing writings critical of the government, and signing open petitions, bloggers and activists visit families of political prisoners or activists in need and provide small but meaningful financial support. They wait at airports to welcome home fellow activists who return from advocacy trips abroad and are frequently detained by police. They go to police stations to demand the release of fellow activists detained for participating in peaceful protests. Brutal repression, including the physical attacks documented in this report, have certainly deterred some in Vietnam from activism, but many others have courageously continued to call for the creation of a rights-respecting democracy.

Back to top

Launch Map

Launch Map