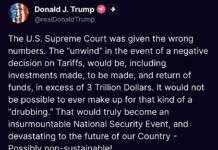

How U.S. Pressure — Not Russian Power — Shapes the Ukraine Negotiations**

In any genuine peace process, the role of a mediator is both delicate and decisive. A mediator is expected to reduce conflict, balance interests, and facilitate dialogue — not to substitute the will of one party for another. Yet the current negotiations surrounding Ukraine raise an uncomfortable question: Is the United States still acting as a neutral mediator, or has it become an enforcer applying pressure on Ukraine that Russia itself cannot?

Question One: Has Russia been able to pressure Ukraine after four years of war?

The answer is clear: No.

For nearly four years, Russia has employed every tool available to a major military power — large-scale invasion, infrastructure destruction, nuclear threats, and cyclical military escalation. Yet none of these efforts have produced the political outcome Moscow sought.

Ukraine has not capitulated. Kyiv has not accepted territorial concessions. Russia has not imposed its terms at the negotiating table.

If Russia possessed effective diplomatic leverage over Ukraine, it would not require a prolonged war. The reality is that Russia lacks meaningful non-military leverage over Kyiv. Its only instrument of pressure remains the battlefield — and even there, it has failed to force political submission.

This failure is crucial. It explains why Moscow increasingly seeks outcomes not through direct negotiation with Ukraine, but through indirect pressure channeled via third parties.

Question Two: If Russia cannot apply pressure, where does the pressure on Ukraine come from?

There is only one plausible answer: the United States.

Not because Washington intends to coerce Ukraine, but because only the United States has the capacity to do so. For years, U.S. influence over Ukraine has rested on decisive pillars:

-

military assistance,

-

intelligence sharing,

-

security guarantees,

-

leadership within NATO.

If Ukraine faces a situation in which it is urged to “accept a deal to stop the war,” that pressure cannot originate in Moscow. It can only come from Washington.

This dynamic produces a dangerous distortion: Russia does not need to coerce Ukraine directly if it can rely on the United States to transmit pressure on its behalf.

This is not mediation. It is delegated pressure.

Question Three: Is this still mediation — or something else?

A genuine mediator does not:

-

use asymmetric power to coerce the victim of aggression,

-

equate the aggressor and the attacked party,

-

frame civilian deaths as leverage in negotiations.

When a mediator employs its political, economic, or military advantage to push one side toward concessions the aggressor could not secure on its own, mediation ceases to exist.

At that point, the mediator becomes an enforcing actor, even if unintentionally.

This is what makes the current situation fundamentally different from traditional peace brokerage. The United States is not merely facilitating talks; it risks becoming the mechanism through which Russia’s failed pressure strategy is outsourced.

Why Ukraine “locks in” the process

President Volodymyr Zelensky’s insistence on institutional constraints is not obstructionism — it is defensive diplomacy.

By demanding:

-

legally binding security guarantees approved by the U.S. Congress,

-

multilateral negotiations involving Europe and NATO,

-

constitutional and referendum requirements for territorial changes,

Ukraine is preventing any single leader or informal channel from imposing outcomes that bypass democratic and legal safeguards.

These mechanisms are designed to ensure that no individual mediator can convert power asymmetry into political coercion.

The broader implications

This issue extends beyond Ukraine. If mediation becomes a vehicle for transferring pressure from an aggressor to a partner, the international system itself is destabilized.

Aggressors learn they need not win wars — they only need to outlast mediators willing to “end the killing” at any cost. Victims learn that survival may depend not on justice, but on the preferences of powerful intermediaries.

Such a model does not produce peace. It produces temporary pauses before renewed conflict.

Conclusion

Russia has failed to pressure Ukraine militarily or diplomatically.

Russia cannot force concessions at the negotiating table.

If Ukraine is pressured to accept terms it did not choose, that pressure does not originate in Moscow — it originates elsewhere.

And when a mediator becomes the source of coercion, peace negotiations transform into instruments of power, not reconciliation.

True peace cannot be built on delegated pressure. It must rest on law, accountability, and consent — or it will collapse the moment power shifts again.