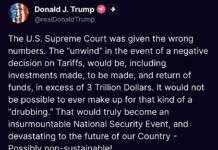

June 25

One year. One year it’s taken me to process. One year it’s taken me to come to terms. One year to find the mind I lost. I think. And I know how today will go, and tomorrow, and the next, and the next after that. It’s so simple. I wish it weren’t. All I can do is breathe. But on the inside I’m not too old for make-believe in these quiet moments I have to myself. The card games, the late shifts I know he’s not working—this is my time.

I hadn’t kept my promise. I couldn’t, and I’d given up at the first hint of doubt. Because if he was real then he didn’t understand—he’d never walked in my shoes or lived in an abusive marriage. And if he wasn’t, then I had no promise to keep. There was no reason to suffer the loss of a ghost, a character created by my own subconscious. After all, I’d never grieved over Laurie or John Willoughby; I’d never wondered what happened to Mr. Tumnus. And I’d certainly spent many more hours with them than I had Tom.

I only ever waited for night, when I could hide with his memory and no one came looking for me. Daytime stripped me of my identity, the hours spent running back and forth cooking the meals, washing Otis’ filthy clothes, keeping him calm day after day, month after month. There was no promise to keep.

But that Friday morning I sat straight up in bed, fidgety like I was forgetting something. The room was warm, the floor, too; I’d slept late. I tiptoed out, careful not to wake Otis, and flipped on the coffee pot, grabbing the newspaper off the porch. On top a bright blue flyer read: “Join us for Fort Benton’s Annual Summer Celebration!” I read it again. Had it been a year already? I thought about the food, the fireworks—a little bit of color might be a nice way to break the monotony, at least for a couple of days.

“Fe, where are you?” Otis hollered from the bedroom, banging his fist on the back wall of the trailer. I scrambled inside, dropping the newspaper on the table.

“I’m here Otis; I was just on the porch.”

“Is breakfast ready?”

“Almost. Your clothes are on the end of the bed.” My shoulders tingled, still fidgety as I fried four eggs for Otis’ breakfast, popped two slices of bread in the toaster, and poured a glass of orange juice, which he would inevitably top off with something perky. I had that feeling in my chest like I needed to hurry, but with nowhere to go. Was it excitement? I couldn’t even remember what that felt like, and had nothing to get excited about, watching Otis plant himself at the table and light his first cigarette.

I scraped breakfast onto his plate and sat down across the table, eyeing him from behind his newspaper as he shoveled forkfuls noisily into his mouth. He flipped slowly through the sports section of the Press, the blue flyer face up next to his glass of juice.

“Good Lord, what a bunch of dumb fucks. You can’t win games without a defense,” most of which I knew he gathered from the pictures and captions. Turn the page, slurp. “Eighteen million for that clown? What a waste.” Turn the page. I stirred my coffee until the steam disappeared. Turn, turn, turn. An eternity spent staring at the classifieds. Jesus. Finally he folded up the paper and leaned back in his chair, crushing the cigarette on the edge of his plate and lighting another.

“Hmm?” he grunted, finally seeing the flyer, flipping it over. “Oh, right.”

“Should we go?” I fidgeted under the table, wondering why I’d asked.

“What, to the Celebration?”

“Yeah.”

He snorted, taking a long drag on his cigarette. “No. I think I’ve had enough fried food and pie auctions to last me the rest of my life. Roger needs me down at the depot anyway, something about extra work he wants done this weekend.”

Sure. I sipped the cool coffee.

“You’re not going, are you?”

“I might.”

“You know I don’t like you going down there alone”—he licked his rotten front tooth—“make it quick.” He wasn’t protecting me; he was protecting his reputation. The whole town knew an absent Otis was a drunk Otis.

“I know.” And that was it. That was the conversation, longer than most we had. I cleaned the kitchen, and he planted himself on the couch, not even pretending to commit to the lie of going in to work. I poured him a stiff drink and left the bottle next the couch knowing that if he finished it then I had several hours to kill. He flipped on the baseball game.

“I may not be here when you get back. Roger’s going to swing by.”

“Yeah, the work thing.” And he topped his glass so high that in a few minutes there would be no such thing as Roger.

I drove down the hill into town, now an expert at ignoring the landmarks I’d memorialized for so many months. I didn’t stop at the railroad tracks or glance longingly through the museum gates anymore, and I hardly remembered the bridge at all. Thousands of visitors had already filled Front and Main Streets with their campers and food trucks, and rows of vendors lined the park with everything from chainsaw art, to jewelry, quilts, windchimes, and a menagerie of iron and blown glass. Chicago dogs hung on the air, and the long line to the Tasty-Freeze wound all the way around the corner. I parked in front of Mom and Daddy’s house and followed a gaggle of noisy grade-school boys into the gates of the park.

“You do it!”

“No, you!” They giggled and ran over to the butcher’s booth, pulling on each other’s shirts and trying not to be first. I peeked over their shoulders and saw a brown wicker basket beside the long list of prices, filled with hundreds of tiny green rubber bands.

“You said you’d do it, you swore.”

“I did not.”

“Shut up, I’ll do it.” The biggest boy reached into the basket, grabbing one of the little bands and popping it into his mouth.

“Gross, he’s eating it! He’s eating the doughnut!” But soon they were all chewing and snickering, bragging that this one had two, and this one had three.

“Hey,” the vendor said, “don’t you go choking on those, my insurance won’t cover it.” But he grinned and I saw green in his teeth, too. Cow doughnuts. The little boys skipped away, gnawing and grabbing their throats, pretending to gag. I picked up one of the little bands and rolled it around in my fingers.

“Cow doughnut?”

“Yes, ma’am,” the man said, a funny look on his face. “You know what they’re for, right?”

“Yeah, I think so. Do you mind if I take a few?”

He waved his hand. “Take all you want, I’ve got a million of them.” I grabbed a handful and shoved them in the back pocket of my jeans, thought for a second, and popped one into my mouth. I could still taste the powder on the rubber, familiar, kind of like the nipple on a baby bottle but very, very chewy. I rubbed my cheek.

“Don’t chew too hard or it’ll give you a jaw ache.”

I thanked the man and walked away, rolling the little doughnut around my teeth and on the tip of my tongue. It tasted all right, nothing like a cow thankfully, but after a bit I stuck it back in my pocket, washing away the flavor with a cherry dip cone.

I wandered in and out of the side streets watching more vendors set up for the long weekend. Tomorrow would be bigger, but I always liked the Friday of the Celebration with its quiet anticipation and all the campers rolling into town. I could pretend for just a moment that I lived somewhere big and important, filled with people and things to do, no longer hidden from the rest of the world behind the tall river bluffs.

Around the corner from the library someone had nailed a sign to a tree that read “Annual Used Book Sale, $1 per book, $5 per bag.” Most of the books were completely obscure—cookbooks with stained pages or muscle magazines, local history and lore—but every so often I’d find a gem and tuck it into my bag, something to keep my mind off things when it got cold again. An old woman sat behind a card table, slumped awkwardly into a folding chair. I handed her a wad of cash to pay for my books.

“Will that be all, dearie?”

“Mm-hm. You can keep the change for the library fund.” When she smiled I knew her immediately: Mrs. Dixon, the librarian. She’d retired years ago and I hadn’t seen her in a very long time. And for a second I wanted to say hello and remind her who I was, but she had that sort of lost look that old people get and I knew she’d never remember me. Long ago she’d been one of the few people to show me kindness, and more importantly, she taught me to think for myself. How many rainy afternoons had I spent curled up in the old wingback chairs, lost in stories of distant lands and buried treasure? Without thinking I reached out and squeezed her hand.

“Yes, dearie, what is it?” her wizened face a question mark. I’d been right.

“No, I’m sorry. It’s nothing.” I let go of her hand. “Thank you for the books.”

“You’re very welcome. Thank you for supporting the library.”

I came home and slipped into my pajamas, stacking my “new” books under the lampstand. I’d wait to read them until things got dreary again and I needed a good distraction. But today felt light, almost happy. Otis had fallen asleep to the baseball game and I noticed he’d opened another bottle, the first empty and on its side. No Roger. It didn’t matter. I shut my eyes and fell back onto the bed, arms wide, and wiggled my toes, still fidgety. I slid open the drawer.

June 25

Cow doughnuts. They chewed them like gum.

Happy.

Outside barred owls and bats darted past the window, silhouetted against the dusty pink sky. Breakfast time.

Somehow when Tom disappeared, so did the nightmares. No more banging and wailing from the attic. No more blood pouring through the cracks. I figured I was so depressed and so numb that my brain couldn’t even create bad dreams anymore. But the emptiness suited me just fine—seeing, hearing, and being nothing felt so much easier, and recharged me just enough to handle one more day at a time. I didn’t want good dreams, not if they left me like this. I’d rather disappear for eight hours and be none the wiser for it.

And for a long time that’s all it was. But that Friday night he came back all of a sudden. Not like before, just a regular dream. But his face was so clear and just right, and I rubbed hard at the familiar ache in my chest. He didn’t say anything, just smiled and held my face in his hands. And then he disappeared, just like before.

Otis stayed home Saturday night, missing the fireworks for some “big game” out of Seattle. He said he didn’t me to go, especially at night; said he didn’t trust the men in town. And why would he? He was one of them. But by the time the sun settled low over the river he was three-quarters deep in a bottle of gin, sinking and farting into the couch cushions. He didn’t know me from a hole in the wall, didn’t have a wife, and I was free to go. And I thought I might, but stepping off the porch felt too heavy. So I sat in the dark instead, grabbing carefully for the mayflies and curling them into my lap.

June 26

They’re back, bringing all the magic with them.

I lay in bed thinking about Otis. He looked so pathetic lying there next to me, breathing hard under the weight of his own girth, pale and smelling like sweat and booze. He used to be so handsome, I thought, remembering the butterflies when he looked at me, wiping motor oil from his hands. He’d hidden the cruelty so well behind those blue, blue eyes, and when I’d finally figured it out it was already too late. He could outrun me, overpower me, take whatever he wanted from me. And now he didn’t have the energy to leave the house. But deep down he was still that guy, the one who needed to hurt me to feel in control. I knew he was losing that battle and he hated himself for it. And so he hated me, too, bitter that I hadn’t fallen apart in the same way. I could take care of myself, leave when I wanted, function without the aid of drink or pills.

My skin had grown so thick I didn’t hear him screaming at me anymore. What could he do? Hit me? He did. Choke me? Not usually; too much work. Call me names? Nothing worse than I called myself. And if I closed the door he had no one. He needed me, and I got a lot of satisfaction knowing how much he hated that, too. What a hollow shell of a man he was, what a waste of a life. He’d wasted most of my life, too, but even so, there were days when I thought I could forgive him.

They weren’t often.

I rolled onto my side wondering when I’d stopped praying. It didn’t matter; I wouldn’t know what to ask. The idea of begging a man, even God, for help after being ignored and thrown to the wolves for so long didn’t appeal to me much. I hugged my pillow, turning away from Otis’ wet breath.

Tap, tap, tap. Tap, tap, tap.

I blinked; my eyes felt dry and sandy.

Tap, tap, tap. Tap, tap, tap.

Something was tapping on the window. I thought about the noises in the attic, but this was something different. I pulled back the blankets and kicked my legs over the side of the bed. Whatever it was darted past the window, left, then right, then hovering at the base of the sill. I leaned over and wiped away the moisture from the warm bedroom. Outside the window the mayflies gathered in flickering little clouds, bumping stupidly back and forth and slamming into the glass over and over again. They’d seen the nightlight coming from the bathroom and were trying to get in.

Tap, tap, tap.

There was that fidgety feeling again, just waiting for something, tugging. The clock blinked 1:30—too late for a cup of tea.

I flipped on the stove light and poured myself a glass of milk, rubbing at the dryness in my eyes. In the dim light I could see yesterday’s newspaper folded up on the table, the flyer sticking out underneath, and Otis’ keys where I’d dropped them on the way in.

Tap, tap, tap.

Mayflies bumped against the kitchen window now, following the light around the side of the trailer. I sat down and drank the milk, fidgeting with the keys. I was forgetting something.

Tap, tap, tap.

I’m sorry, Fe. It’s always like this.

I heard his voice as clear as day. I’d nearly forgotten. And just like that, there he was again. I drank the last of the milk and tiptoed into the bedroom, listening to Otis breathe for a minute before reaching quietly into the drawer and grabbing the journal. I tucked it under one arm, tied my shoes, and brushed my teeth.

1:45.

Then I remembered the handful of little cow doughnuts and scooped them up out of the hamper, shoving them into the pocket of my pajamas. I didn’t know where I thought I was going, but I grabbed the keys and left, inching the pickup quietly down the driveway, then gunning it onto the highway and coasting down the hill. Slowly up and over the tracks, left at the football field, right at the pool, down along the park to the river.

I flew past darkened house after darkened house, all fast asleep in their beds, and inched around the roundabout in front of the Tasty-Freeze and onto Front Street. Mayflies flew past in waves, caking my windshield in a sticky film, and I could barely see the one blurry red stoplight blinking at the other end of town. I rolled to a stop in front of the Coast-to-Coast and cut the engine, waiting for something to happen.

June 27

You wanted to decide. So now you need to choose—is this a dream or not? You can go home. Or you can try again.

I climbed out and shut the door, the metal echoing down the empty street. From far away I could hear the soft click, click, click, of the stoplight blinking on and off in the darkness, but I couldn’t see anything else moving down by the old hotel. There was no breeze tonight, and the mayflies cluttered and clumped on every surface, every pole. I squinted, looking as far as I could in the other direction toward the park.

Nothing.

I thought about going up onto the bridge. Maybe if things were exactly the same, or nearly, I could sort of recreate the whole premise and start the dream from the very beginning. But I remembered what it felt like drowning at the bottom of the river. And besides, there was no flood this year—I’d probably just break my leg and end up limping home. Maybe I could walk to the park where he’d been watching the last time. Or maybe I should get back in the truck and go home.

But I’d heard his voice. It wasn’t a memory; I’d heard it. Hadn’t I?

The river path was littered with streamers, candy wrappers, and beer cans, and somewhere across the river a coyote howled. I thought about the railroad tracks, the disappointment. I didn’t need to keep doing this to myself. But whatever it was wouldn’t let me stop—I’d let the memories out so far I couldn’t stuff them back in. And they were just as raw and painful, and so clear in my mind. He’d never faded away.

The neon sign blinked CLOSED in the Tasty-Freeze window and I walked quietly around the roundabout, trying not to ruin the perfect stillness with my footsteps. Beside me the river followed at a slow, sleepy pace, low and dry after a weekend without storms, and I could hear the carp jumping for mayflies far out in the water. Whizz…plop. One mayfly down. Whizz…plop.

I stopped to listen. The sound wasn’t coming from out in the river; it was somewhere close to the banks.

Whizz…plop.

I walked across the boat launch and down to the levee, careful not to make a sound in the gravel as I tiptoed toward the water. I peered over, staring into the dark and waiting for my eyes to adjust. Someone was sitting on the floating dock with his feet in the water, fishing.

“Hey Fe,” a voice said. “You came back.”

Copyright© 2025 Eleanor Leonard All Rights Reserved

Ellie is an author, editor, and owner of Red Pencil Transcripts, and works with filmmakers, podcasts, and journalists all over the world. She lives with her family just outside of New York City.