Investigative Report — (English edition for international organizations)

I. Introduction: Land as Power, and Media as the Instrument

In Vietnam, land is not merely real estate; it is the primary economic resource, the foundation of rural livelihoods, and the largest source of capital for both local governments and private enterprises. Yet, for more than three decades, the country has operated under a dual land-pricing system:

- the State price, used for compensation when land is seized,

- and the market price, used when the same land is sold for commercial development.

This system has produced one of the most extreme wealth-transfer mechanisms in Southeast Asia: farmers lose their ancestral land for pennies, while local authorities and affiliated companies gain billions.

But this machine requires one critical element to function smoothly:

a tightly controlled media system capable of manufacturing social consent while suppressing dissenting voices, particularly those of dispossessed farmers.

During Vietnam’s early Đổi Mới (Reform) era, no figure embodied this media-political nexus more clearly than Nguyễn Công Khế, known informally as:

“The Media Hawk.”

He is not the root cause of the system—but he is a revealing symptom: a charismatic, powerful newspaper editor who wielded enough influence to pressure ministers, shape national debates, and sway policy discussions on land governance.

This report examines:

- how land became the core of Vietnam’s political-economic power structure,

- how media was co-opted into legitimizing land grabs and protecting elite interests, and

- how figures like Nguyễn Công Khế rose within that system.

II. Vietnam’s Reform Era: Semi-Controlled Liberalization and the Illusion of Open Debate

From 1986 onward, Vietnam embraced market reforms while retaining one-party rule. This hybrid model required a carefully engineered media environment:

- open enough to simulate public debate,

- but controlled enough to prevent any challenge to the Party’s monopoly over land and political power.

Thus emerged the concept of:

“Managed pluralism” — controlled diversity of opinion.

Newspapers were allowed to:

- raise questions about governance,

- debate economic policies,

- uncover low-level corruption,

—but were forbidden from challenging systemic pillars:

- the Party’s control over land allocation,

- the one-party political structure,

- the top tier of leadership,

- and, importantly, land laws that grant the State total ownership.

Within this controlled ecosystem, powerful editors became brokers between the political elite, business tycoons, and public opinion. They helped shape what the public was allowed to know—and what it was not.

III. Land: The Central Pillar of Power in Contemporary Vietnam

Land is where political power, economic interests, and state violence intersect.

Why land is pivotal:

- 65–70% of Vietnam’s population relies on agriculture.

- Local governments fund themselves primarily through land conversion and auctions.

- Banks depend on land as collateral.

- “State-linked” developers rely on cheap land to build new urban zones.

The Law on Land (which declares land is owned by “the People” but managed entirely by the State) turns local officials into de facto landlords.

This system produces massive profit margins:

- Farmers receive as little as USD 10–20 per m² in compensation.

- After rezoning, developers sell the same land for USD 1,000–3,000 per m².

- Profit margins often exceed 200x to 300x.

These windfalls are shared between:

- local authorities,

- provincial officials,

- and private corporations known as “sân sau” (“backyard” companies).

To justify this scheme, the State needs a media system that:

- magnifies pro-government narratives,

- suppresses dissent,

- delegitimizes protesting farmers,

- and gives political cover to violent land seizures.

This is where powerful editors played an essential role.

IV. Nguyễn Công Khế – Portrait of a “Media Hawk”

Nguyễn Công Khế, born in 1957, became the Editor-in-Chief of Thanh Niên (Youth Newspaper) — one of Vietnam’s most influential publications.

Under his leadership:

- Thanh Niên achieved nationwide dominance,

- cultivated close ties with top officials,

- shaped public debates on land and development,

- and became the platform many policymakers sought for agenda-setting.

Journalists describe him as:

- charismatic,

- politically connected,

- feared within the industry,

- capable of calling ministers to demand headline revisions.

A common saying in southern journalistic circles was:

“One phone call from Khế carries more weight than a government decree.”

While partly hyperbolic, it reflects how media influence in Vietnam is often personalized and intertwined with political networks.

Khế did not create the system—he mastered it.

V. Case Study: The 1995 Decree 18/CP and the Media Pressure Campaign

One of the most revealing episodes was the dispute over Decree 18/CP (1995), signed by Prime Minister Võ Văn Kiệt. The decree implemented:

- stricter taxation on land use,

- mandatory land leasing for companies,

- and clearer accountability for land-based businesses.

This threatened profits for:

- district-level construction companies,

- land speculators,

- and officials benefiting from informal land redistribution.

Immediately after the decree, several major newspapers launched a coordinated campaign criticizing it—labeling it an obstacle to urban development.

Among them:

- Thanh Niên under Nguyễn Công Khế,

- Sài Gòn Giải Phóng,

- and various state-linked economic papers.

The narrative construction: “Reform is hindered by outdated rules.”

A single dissenting article appeared in Phụ Nữ TP.HCM (Women’s Newspaper), written by journalist Mai Bá Kiếm. He argued:

To amend the decree, one must amend the underlying ordinance issued by the Standing Committee of the National Assembly.

In essence, the media’s attack on the decree was legally baseless.

The response?

Nguyễn Công Khế immediately called the editor-in-chief of the newspaper and reprimanded her:

“Why did you let him publish an article opposing my newspaper?”

This incident illustrates how policy debates were not driven by public interest, but by media factions aligning with political-economic interests.

VI. “Fake Consensus”: How State-Controlled Media Manufactures Public Support

Vietnamese state media commonly uses several methods to manipulate public perception:

1. Curated public comments

Only pro-government comments are published. Critical opinions are filtered out.

Typical headlines include:

- “Most citizens agree with the electricity price hike.”

- “Residents support land clearance for development.”

In reality, no representative survey is conducted.

2. “Green commentators” (quân xanh)

Commentators from affiliated agencies are instructed to post supportive opinions to give the appearance of public endorsement.

3. Selective expert voices

The same “experts” appear repeatedly, always supporting government decisions.

Independent economists or land rights lawyers are excluded.

4. Manufactured urgency

Media often frames land seizures as necessary for:

- “modernization,”

- “national development,”

- or “public interest.”

Even when the land is ultimately handed to private developers.

This propaganda-legitimized land grab mechanism has fueled dozens of violent conflicts, including:

- Dương Nội,

- Văn Giang,

- Thủ Thiêm,

- Lộc Hưng,

- and Đồng Tâm.

VII. The Cost: Farmers Dispossessed, Journalists Silenced, and the 1% Enriched

1. Farmers pay the highest price

Across Vietnam:

- millions have lost farmland,

- hundreds of thousands have been displaced,

- many communities fall into debt and unemployment,

- some individuals commit suicide after losing their property.

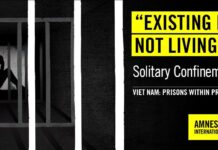

2. Journalists who expose land corruption are imprisoned

Notably:

- Phạm Đoan Trang (journalist) – sentenced to 9 years.

- Cấn Thị Thêu and her two sons (land rights activists) – repeatedly jailed.

- Dozens of independent reporters arrested for documenting forced evictions.

3. The elite 1% enrich themselves

Land seized at USD 1–5/m² is resold for USD 1,000–3,000/m².

The profits fuel:

- political patronage networks,

- local government budgets,

- and the rise of a new oligarchic class.

VIII. Nguyễn Công Khế – A Symptom of Structural Media Capture

International observers should recognize that Nguyễn Công Khế is not an anomaly. He is:

- the product of a hybrid authoritarian media system,

- the representative of a model where editors serve as political intermediaries,

- and a figure who demonstrates how journalists can be weaponized to facilitate land dispossession.

He symbolizes:

the transformation of journalism from watchdog to enabler.

IX. Conclusion: When Media is Bent, Justice Cannot Stand Straight

Vietnam’s land regime—combined with systematic media manipulation—has produced:

- widespread human rights violations,

- the erosion of rural livelihoods,

- the criminalization of protest,

- and the consolidation of political-economic privilege.

No land reform will succeed without media reform.

No media reform will succeed without political reform.

And no justice can be achieved while the voices of journalists and dispossessed farmers continue to be silenced.

To understand Vietnam’s land conflicts, international organizations must analyze not only land laws, but also media capture, political pressure, and the structural function of newspapers as tools of state power.

Only then can the global community fully grasp the dynamics that have shaped some of the most serious human rights crises in Vietnam’s modern history.